Video by by Vladimir London

Enroll in the Life Drawing Academy now!

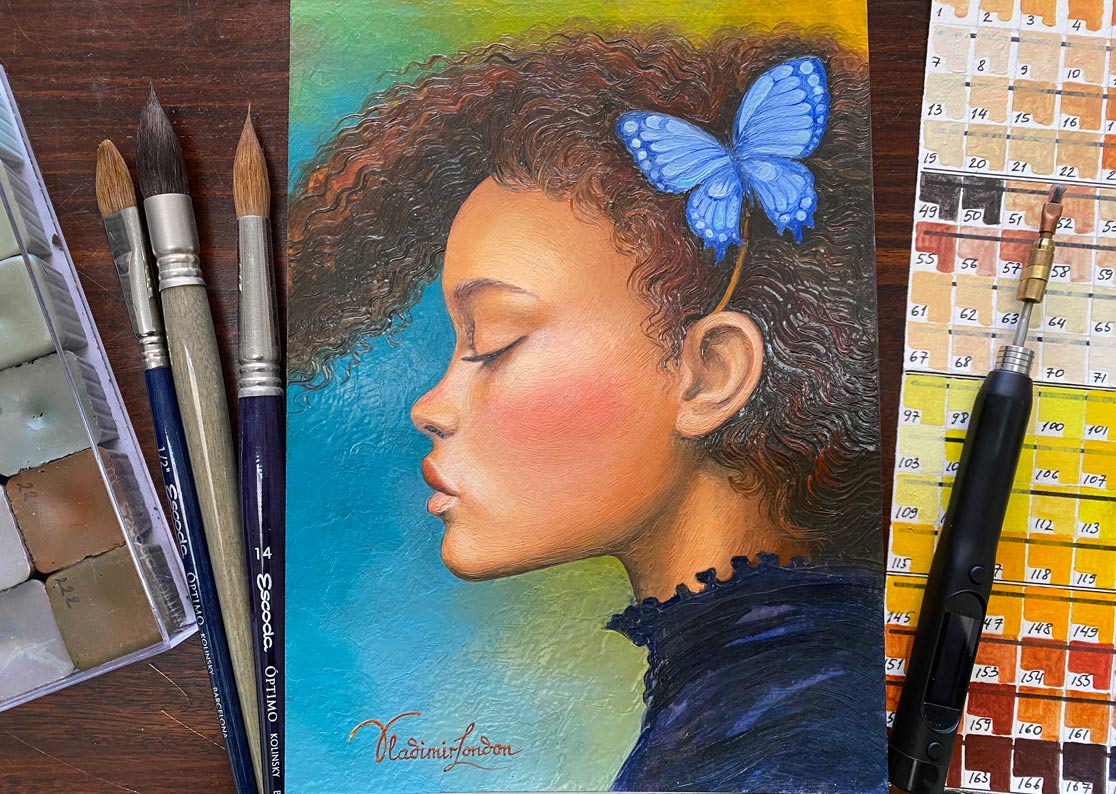

Encaustic Portrait Painting by Vladimir London

In this video, you will see the complete process of making a portrait in encaustic on paper. I chose paper to experiment with whether this medium is appropriate for hot wax painting. I plan to create a series of small encaustic portraits, and this is the second on that list.

Prior to applying beeswax paints, I need a colorful underpainting. Watercolor is very much suitable for this task. Since both watercolor and encaustic mediums are transparent, I have to protect the white paper from erasing and redrawing, as it could harm the surface. Therefore, this sketch was initially designed as a cartoon and then transferred to the watercolor sheet. You can learn how to draw portraits in the Life Drawing Academy course.

I also provide guidance on applying constructive drawing techniques, anatomy, and proportions for portraiture through various video tutorials and in my book titled "How to Draw a Portrait in the Three-Quarters View," which is available in multiple formats on Amazon. Currently, I am using a plain wash to apply a single color across the entire face area. This piece will be created using encaustic techniques, allowing for a very simple watercolor underpainting without the need for complex gradations or intricate washes, retouching, or other advanced methods. The goal of this underpainting is to establish basic colors and tonal values, making the subsequent application of beeswax paints easier and avoiding the use of thick impasto layers. Since watercolor paper is flexible, I cannot apply heavy layers of wax; however, thin encaustic layers would be too transparent to adequately cover the white surface with the desired saturation and tonal values. This initial watercolor layer will significantly aid in achieving the necessary hues and chiaroscuro effects. Additionally, I am not hesitant to go slightly darker at this stage, as the watercolor will lighten upon drying, and I can wash out certain areas before it fully dries to achieve lighter shades. Meanwhile, I carefully paint around the highlights and eyes to maintain the white of the paper, as washing out does not restore the original brightness.

For this wash, I utilize a premium mop brush from Escoda, which you can find at their website. I appreciate Escoda brushes because the company is dedicated to producing high-quality tools. This particular mop brush is excellent at holding a substantial amount of paint and releasing it smoothly, allowing me to create both fine and broad brushstrokes with precision. If you're interested in mastering watercolor painting like a professional, I recommend visiting the Watercolor Academy website. They offer two types of courses: online and correspondence. The online course provides lifetime access to 80 detailed video lessons covering essential topics for aspiring artists, including material selection, color theory, various techniques, and how to paint different subjects, from still lifes to portraits. Additionally, this course includes unlimited support, offering critiques of your artwork and guidance on improving your skills. For those truly committed to becoming skilled watercolor artists, the Watercolor Academy Correspondence Course is the best option available. It offers unlimited personal tutoring tailored to your individual skills and needs, along with 100 practical assignments covering all necessary topics to help you become proficient in watercolor painting. This level of personalized instruction is unmatched by any art college, especially for such a reasonable one-time fee. We guarantee that by the end of this course, you will have developed advanced watercolor painting skills. Currently, I am diluting the first layer and washing out paint in certain areas. This technique allows me to achieve a rough chiaroscuro effect more quickly than if I were to apply multiple layers of transparent glazing and wait for each to dry before adding the next. While I wouldn't use this method for a watercolor portrait, it works well for my current project.

Creating this encaustic piece allows me to explore whether wax paint can be applied directly onto paper without the need for a layer of ganosis. Ganosis, which I prepare using a specific recipe, is an unpigmented beeswax medium made from bleached beeswax, natural resins, and linseed oil. It remains solid at room temperature and must be heated for application. This medium acts as a sealant, protecting the surface from moisture, air, and temperature fluctuations, functioning both as a varnish and an adhesive that secures encaustic paints to the substrate. While encaustic paints are theoretically expected to bond well with paper, I am curious about their long-term effects on the material. The fatty acids in natural beeswax might potentially weaken the paper over time or diminish the binding strength of the encaustic medium. Although creating swatches of encaustic paints on paper with and without ganosis is a straightforward testing method, my focus is on practicing portrait painting in encaustic. This experiment doubles as an artwork that could endure for centuries or deteriorate within a few years; only time will reveal the outcome. Currently, I am working on an abstract background using a variegated wash, where various colors blend and flow into one another. The soft transitions of hues create a decorative effect, hinting at a vibrant backdrop behind the subject's head. I may alter the colors when painting in encaustic later, but for now it will do.

After experimenting with various encaustic painting techniques, including underpainting with both polychrome and monochrome approaches, as well as using verdaccio and grisaille methods, I have concluded that a colorful underpainting is crucial for encaustic artwork. It significantly enhances the overall color dynamics and tonal values of the final piece.

Focusing on the small details during the underpainting phase is less crucial than considering the overall colors and values, as it's quite easy to get caught up in fine details when working with wax medium. However, watercolor is excellent for creating intricate details, so I recommend spending a few moments on features like eyes and other facial characteristics. Once the underpainting is finished, it's time to layer the portrait with encaustic. For this, I utilize my homemade encaustic brush, the Vladimir London Cauterium. This tool features an electric pen that precisely heats the tip to the desired temperature. The tip, made of copper for its excellent thermal conductivity, is held in place by a brass holder that allows for easy tip changes. To enhance the absorbency of the cauterium, a very fine tungsten wire is wrapped around it. Although tungsten conducts heat less effectively than copper, its mechanical properties make it ideal for this application. The wire is just 0.08 mm in diameter, comparable to natural hog bristles, ensuring that the texture of the brushstrokes remains consistent with traditional brushes. Additionally, tungsten is highly resistant to wear, oxidation, and tarnishing, making it an excellent choice for encaustic brushes. The tip reaches around 80 degrees Celsius, while the heating element itself is set to 130 degrees, with a temperature drop of 50 degrees occurring as heat transfers through the brass, copper, and tungsten to the encaustic paint. This temperature is sufficient to melt the encaustic, keeping it liquid until I apply it to the paper. The medium solidifies almost instantly upon contact with the cold surface, and you can observe each brushstroke turning matte within just two to three seconds. In fact, the paint dries in mere seconds, making encaustic one of the fastest drying mediums in art. This quick drying time is a significant advantage, but it also presents its own set of challenges. Here are the transparency samples of my homemade encaustic paints. Each small sample is applied over a black line, making it easier to identify whether the paints are transparent, semi-transparent, semi-opaque, or opaque. Each sample is also numbered to facilitate cross-referencing with the chart and paint blocks.

These paints consist of a wax-based binder combined with pigments. The binder is made from bleached beeswax and three types of natural resins, along with a small amount of linseed oil. The melting point of this medium ranges from 75 to 90 degrees, depending on the specific formulation, which is higher than the melting point of natural beeswax, approximately 64 degrees. This encaustic medium is blended with non-toxic, heat-resistant dry powder pigments that are safe for both health and the environment. My color palette primarily features earth pigments.

I have around 300 different encaustic paint colors in my collection. This extensive variety of tints and shades serves a purpose. Typically, an artist will use several paints and mix the desired colors on a palette or directly on the canvas. According to color theory, all colors can be created from three primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. Mixing any two primary colors yields a secondary color; for instance, yellow and red create orange, red and blue produce violet, and blue and yellow combine to form green. The secondary colors—orange, violet, and green—can then be mixed with adjacent primary colors to create tertiary colors, which can further be blended to generate an endless array of color variations. However, in practice, achieving this requires very pure primary hues, as pigments often carry some undertones. For instance, yellow can be slightly altered towards either the green or red spectrum, resulting in chromatic grays when different colors are blended. Despite this challenge, there's another reason I require a wide variety of pre-mixed colors. Unlike watercolor, acrylic, or oil paints, encaustic medium dries rapidly. To maintain its mixability, it must be heated beyond its melting point, which necessitates using a hot plate for mixing instead of a traditional palette. Additionally, mixing colors directly on the painting surface can be quite difficult. To address this issue, I devised a practical solution: rather than mixing encaustic paints on the spot, it's more efficient to prepare various color blocks in advance and utilize them as needed without palette mixing. This approach offers several advantages. Primarily, it saves time, as grabbing a ready-made encaustic paint is much quicker than mixing. Artists familiar with watercolor know that a significant amount of time is often spent on color mixing, sometimes equal to the painting itself. By bypassing this step, the painting process can be completed in half the time. Another benefit of using pre-mixed encaustic colors is that it eliminates the need for a mixing palette, which can be hazardous since it requires heating to over 80 degrees Celsius—similar to having a hot pan constantly nearby. Moreover, encaustic contains resins, and inhaling its hot fumes can be harmful to health. Therefore, maintaining a hot plate with melted encaustic paints is not ideal for a safe working environment. A better alternative is to melt a tiny amount of premixed encaustic paint using an electric brush, which reduces fumes, accelerates the painting process, and simplifies the overall experience.

When discussing health safety, it's crucial to identify which pigments are safe for use and which ones are unsuitable for hot encaustic techniques, as some pigments can become toxic when heated. Therefore, they should be avoided in wax painting.

For my small-scale artworks, I prefer using smaller encaustic brushes. Over the years, I've created several generations of hot brushes specifically for wax painting. Currently, I utilize a cauterium, but I also have a variety of other brushes, including bristle brushes, felt-pen brushes, and cartridge brushes, many of which I have designed and crafted myself, making them unavailable for purchase elsewhere. The sizes and shapes of these tools differ significantly; I have both round and flat brushes in various dimensions, with the smallest round brush measuring less than one millimeter in diameter and the largest flat brush reaching one inch. I typically reserve the wider brushes for creating abstract backgrounds, as the rigid one-inch brush isn't ideal for intricate details. After refining my hot encaustic tools through six generations, I've developed a versatile selection that meets all my artistic needs. Each brush serves a unique purpose; for instance, bristle brushes are designed to hold just the right amount of wax medium for short strokes, while cartridge brushes can carry enough paint to create a continuous line over 15 meters without needing a refill. Additionally, bristle brushes are excellent for impasto techniques, while cauterium brushes allow for the application of very smooth, thin layers. This variety provides incredible flexibility in my encaustic painting process.

Encaustic painting, being a transparent medium, benefits greatly from the technique of optical mixing. Unlike direct painting, where colors are blended on the palette, optical mixing involves layering transparent paints, with each layer enhancing the overall color effect. For instance, when red and yellow are layered, they create a vibrant orange that differs from mixing the same colors directly on the palette. This variation occurs because light passes through the transparent layers, interacting with the pigment particles before reflecting off the white surface beneath. This journey of light results in a unique visual effect, distinct from the light reflected from a single layer of opaque paint. Therefore, establishing a colorful underpainting is crucial, as it significantly impacts the final appearance of the artwork. It's also advisable to use an underpainting that allows the brightness of the ground to shine through, which is why I prefer watercolor for this initial step.

However, working with encaustic wax in layers presents its own set of challenges. The encaustic medium solidifies but never fully dries, meaning it can be melted and reworked at any time. This characteristic contrasts with oil or acrylic painting, where a fully dried layer allows for easy application of new paint without disturbing the underlayer. In encaustic painting, the underlying layers remain malleable, making it possible to revisit them with heat. This aspect can be particularly daunting for artists; without the right tools and skills, managing the wax medium can lead to frustration. Each brushstroke risks disturbing the previous layers, potentially removing paint down to the ground. The transparency of encaustic paints exacerbates this issue, as any mistake becomes immediately visible, showcasing a different texture and value. Correcting these errors often requires re-diluting the paint surface, but subsequent brushstrokes may only worsen the situation rather than resolve it. I recall my own struggles during my early days of encaustic painting, navigating these complexities.

Creating artwork can be fraught with pitfalls that can compromise its integrity. For instance, when beeswax paints are overheated, they can become uncontrollable and run. Excessive heat can also lead to the evaporation of long-chain fatty acids, altering the chemical composition of the medium. This change can weaken the binder, resulting in the paint layer flaking off over time. I've observed encaustic artists who, perhaps unaware of these risks, use open flames to manipulate beeswax paints. Some even ignite their pieces to create decorative bubbles and streams of wax, which may appear visually appealing but ultimately result in compromised works that lack both aesthetic value and sound technique.

An alternative method for encaustic painting involves using a natural hog bristle brush along with a hot air gun, though I find this technique less than ideal for several reasons. Firstly, it requires both hands to be occupied, demanding intense focus on the process. This makes it easy to accidentally overheat certain areas, causing the wax to liquefy and run uncontrollably. The constant noise from the air gun can be quite distracting, and after several hours of this method, one is likely to end up with a headache. More importantly, this approach poses health risks, as encaustic paints must remain melted in pans or on a hot plate, leading to continuous inhalation of resin fumes, which can be harmful. Lastly, achieving fine, delicate details is challenging when using a hog brush that needs to be heated with a hot air gun. This technique is better suited for large-scale abstract works where precision is less critical, which may explain the prevalence of abstract encaustic pieces compared to finely crafted portraits and figurative art. Ultimately, this painting method can restrict an artist's creativity and shape the outcomes of their work. There are alternative methods for working with encaustic paints that I personally do not employ. One such technique involves using a hot iron to spread the wax. This approach leans more towards craft than fine art, as an iron is not the ideal tool for achieving the fine, precise brushstrokes that are often desired. While it might be possible to create a large, expressionistic portrait with an iron, it would certainly not compare to the traditional masterpieces crafted by the Old Masters. My focus, however, is on reviving the ancient practices of realistic encaustic art. This medium has a rich history, originating in Greece over two thousand years ago. The exact inventor of encaustic techniques remains unknown, but the ancient Greeks used the same term for both beeswax and paint, suggesting that every painter of that era was familiar with encaustic as it was the primary medium of the time. As Greece expanded its influence, the knowledge of encaustic painting was shared with Egyptian and Roman artists. Although no encaustic works from ancient Greece have survived, numerous beeswax portraits from Egypt can be found in museums worldwide. These artifacts, known as Fayum portraits, were first uncovered in the Fayum region near the Nile and were hidden in tombs for nearly two millennia. They adorned the mummies of individuals from various backgrounds—Egyptian, Greek, and Roman—who held significant status in ancient society. A fascinating aspect of mummy portraiture arose when the Roman elite embraced Egyptian customs, choosing mummification over cremation for their deceased.

Ancient Egyptians decorated their sarcophagi with painted plaster masks, while the Romans had a rich history of portrait painting, primarily using encaustic techniques. It is thought that Fayum portraits were created while the subjects were still alive, showcasing a realistic style that captured their true likeness and character. This tradition of Fayum portraits emerged in the first century and continued for approximately 300 years until the decline of the Roman Empire. Over this period, the quality of portrait painting gradually diminished, and by the fourth century AD, Fayum portraits had become less intricate compared to their earlier counterparts.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire, encaustic art did not vanish; instead, it transitioned into Christian iconography. However, the techniques associated with encaustic painting were eventually lost, and by the early Renaissance, artists had abandoned this medium. Leonardo da Vinci attempted to revive the beeswax painting methods, but his effort to create a mural in Florence was unsuccessful due to his lack of knowledge about properly burning in the encaustic, which led to the destruction of his work from overheating. It wasn't until the 17th century that artists and scholars began to rediscover the secrets of beeswax painting, and this knowledge gradually spread throughout Europe and America over the next 300 years. My exploration of the history of encaustic painting indicates that its origins traveled from Italy and Greece to France, Germany, and Belgium, then to Austria and England, and eventually reached Mexico and North America.

In the 20th century, numerous recipes for encaustic paints emerged, with various artists experimenting with this medium to create both easel and monumental artworks. The techniques of encaustic painting evolved significantly with the advent of electricity and the introduction of electric heating tools. Despite these advancements, encaustic remains a somewhat niche medium, and many artists find it challenging to work with.

While I don't claim to have unearthed the ancient secrets of encaustic, I aspire to contribute valuable insights to its rich history. I have created a selection of encaustic brushes that were previously unavailable. One notable innovation is the Vladimir London Encaustic Felt-Pen, which allows for smooth brushstrokes in very thin layers. This hot brush transforms wax painting by enabling the application of glazing layers without disturbing the underlying ones, facilitating techniques like optical color mixing. Additionally, the combination of the cartridge pen and felt-pen enables the creation of long brushstrokes while layering, thus accelerating the painting process. I also designed a brush that revolutionizes the painting of large-scale murals; it features a natural hog bristle tip heated by a flow of warm air, eliminating the need for a hot palette and separate hot air gun. This makes it easy and efficient to paint large artworks. I plan to create a dedicated video showcasing my encaustic brushes, so be sure to subscribe to this channel for updates when it becomes available.

I have developed several small innovations aimed at enhancing the creation of encaustic artworks. These innovations encompass new formulations for ganosis and encaustic mediums, as well as novel approaches to treating and utilizing grounds and supports. I delve into these advancements in detail in my upcoming Book on Encaustic, and I will share the release date in a separate video announcement.

Over the years, I have explored various encaustic painting techniques and drawn some intriguing insights. For instance, the Punic wax referenced by Pliny the Elder and Vitruvius may not be as crucial for modern encaustic painting, as its formulation was intended for cold-wax techniques rather than the hot-wax burning-in method. With appropriate tools, cold wax painting becomes unnecessary since encaustic paints can be easily blended and applied across both small and large surfaces. Ancient texts, including those by Homer, indicate that Greek ships were painted with a beeswax-based medium, yet the precise treatment of this medium remains a mystery. I conducted experiments with different beeswax formulations to assess how Mediterranean Sea water influences ganosis and beeswax paints. My findings revealed that cold wax mediums tend to have a shorter lifespan compared to hot encaustic, likely due to the superior resistance of unbroken long-chain fatty acids to metal soap-laden waters. This suggests that artworks created with hot encaustic are more resilient to humidity and temperature changes, potentially ensuring their longevity over those made with certain cold-wax mediums. I have not encountered any similar studies, which leads me to believe that my research contributes significantly to the existing body of knowledge accumulated over the centuries.

I believe the encaustic medium holds significant importance in the world of art. Artists have developed a variety of paints, such as watercolor, tempera, oil, and acrylic, but when we focus on those that can withstand water, the options narrow considerably to oils, acrylics, and synthetic resins. Oils tend to darken and yellow over time, becoming brittle and prone to cracking and flaking. Acrylics, while popular, have not been around long enough to fully assess their longevity, and many museums are already encountering challenges with the premature deterioration of acrylic pieces. Similarly, synthetic resins raise concerns akin to those of acrylics. In contrast, beeswax encaustic has proven its durability over centuries, as evidenced by the Fayum portraits that have survived for two thousand years, maintaining their vibrant colors and texture. If you aspire for your artwork to endure for millennia, exploring the ancient encaustic medium could be worthwhile. With this perspective, I am dedicated to refining my encaustic painting techniques, hoping that my insights will benefit fellow artists like you.

This artwork is nearly complete. I will enhance its appearance by buffing it with a soft microfiber cloth, which will bring out the natural shine that only beeswax and natural resins can provide. I hope you found this video engaging. For more content on encaustic painting techniques, consider subscribing to this channel. You can also explore my other encaustic creations at vladimirlondon.com/encaustic.

To learn good drawing techniques, enroll in the Life Drawing Academy course:

Online Course

A self-study, self-paced course for you to learn fundamental methods of classical drawing and improve life drawing skills by watching video lessons and doing assignments

- Unlimited access to 52 life drawing video lessons

- Lifetime membership without deadlines

- Unlimited support from the Academy tutors

- Constructive critique of your artworks

- Member access to the Academy's Art community

- Place in the Academy's Students Gallery

- Exclusive members-only newsletter and bonuses

- Life Drawing Academy Diploma of Excellence in your name

One-time payment - Lifetime membership

$297 USD

Personal Tutoring Online + Online Course

The ultimate choice if you who would like to receive personal, one-to-one tutoring from the Academy teachers, which is custom-tailored to your skills and needs

- Everything in Online Course, plus:

- Dedicated team of art tutors

- Assessment of your current level of drawing skills

- Personalized curriculum tailored to your skills and goals

- Up to 100 drawing tasks with by-task assessment

- Unlimited one-to-one personal coaching with detailed per-task instructions and feedback

- Artwork critiques and results-oriented guidance

One-time payment - Lifetime membership

$997 USD