Leonardo da Vinci - The Great Old Master

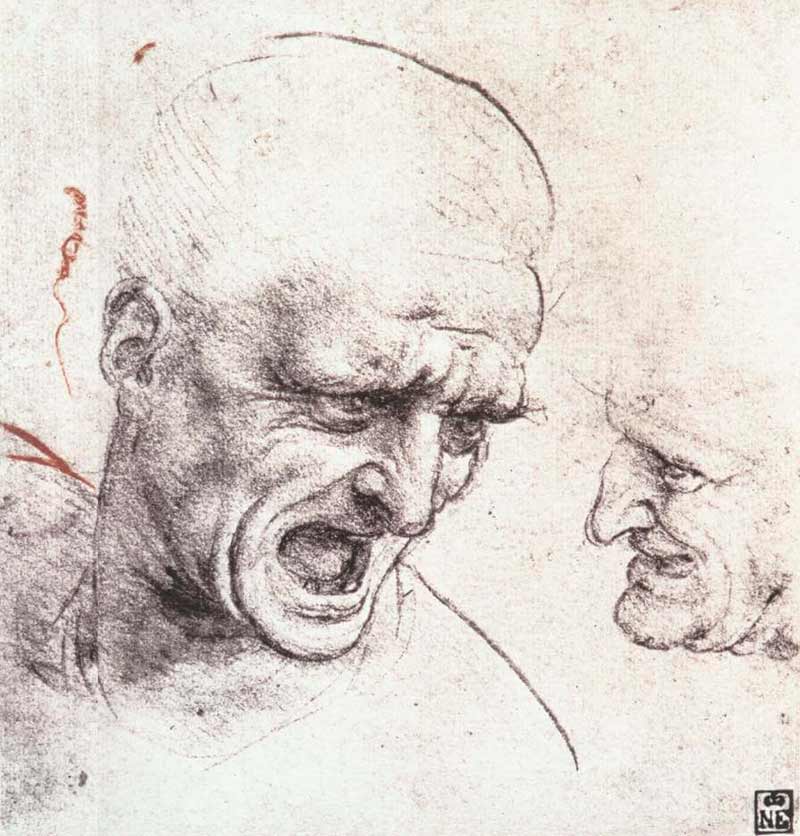

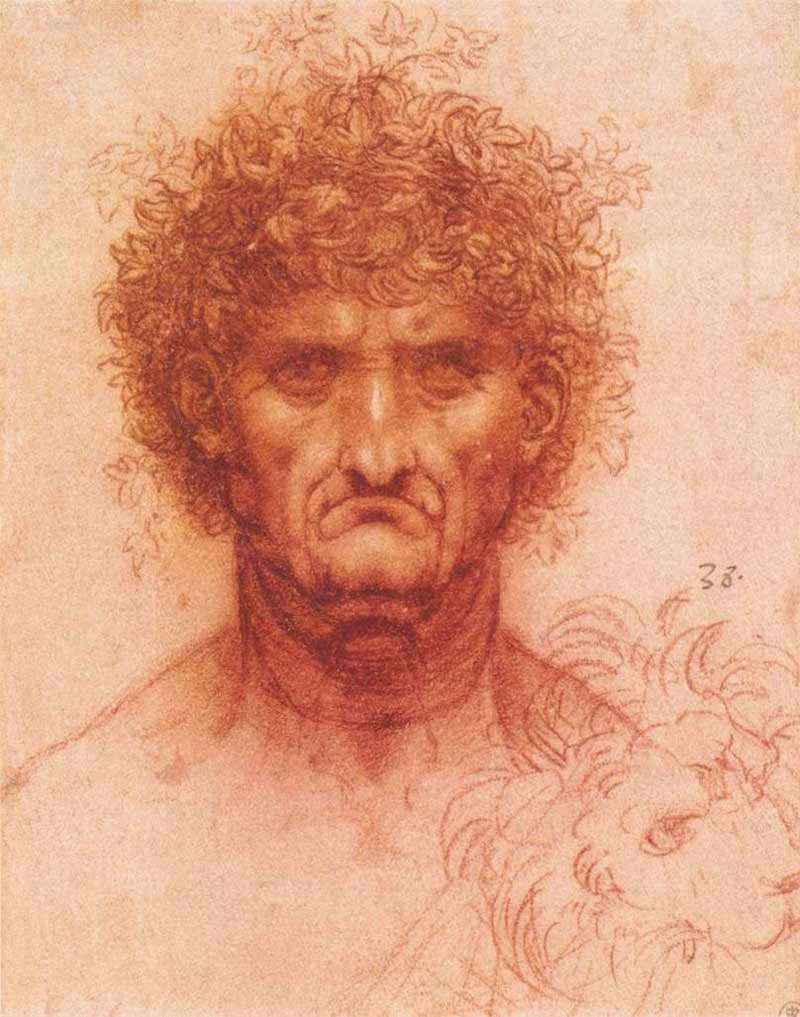

Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by the human body, as is demonstrated by the numerous anatomical studies and life drawings he completed throughout his career. This interest in human anatomy was not unique to da Vinci, but was prevalent with many artists of the period. In the 1435 treatise Della Pittura, theorist Leon Battista Alberti encouraged painters to construct the human figure as it exists in nature, demonstrating how it is supported by the skeleton and musculature, and then clothed in skin.

Leonardo's initial interest in anatomical study probably stems from his apprenticeship in Verrocchio's workshop. Verrocchio himself was interested in studying human anatomy, however, his neighbor, Pollaiuolo, was renowned for his fascination with the workings of the human body, and likely influenced Leonardo's own interest.

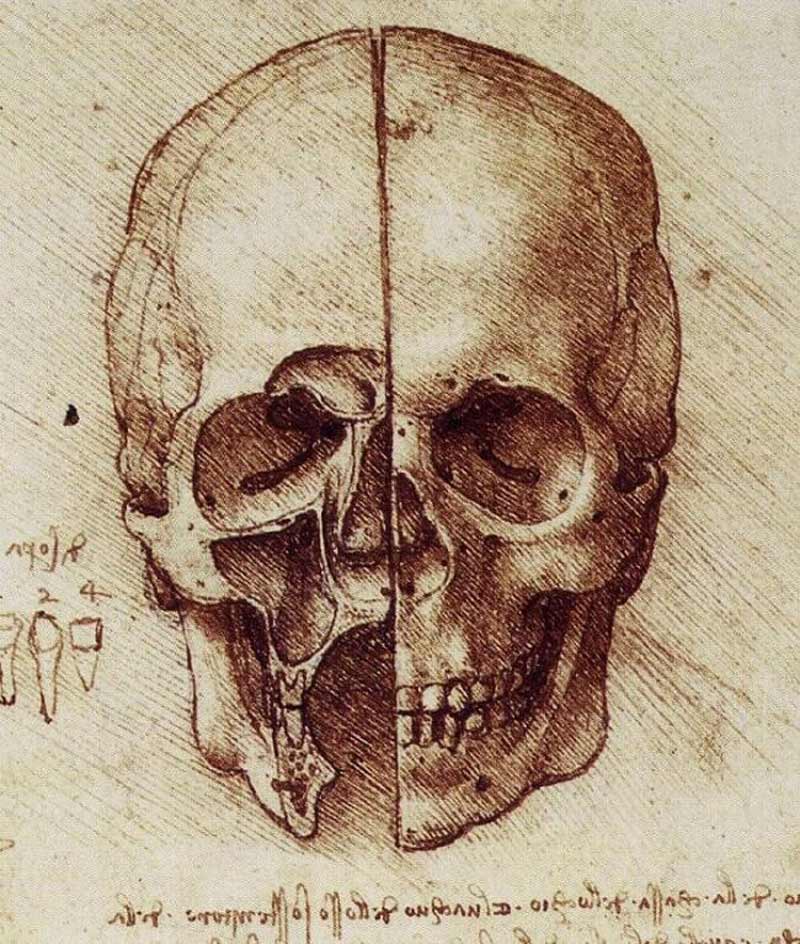

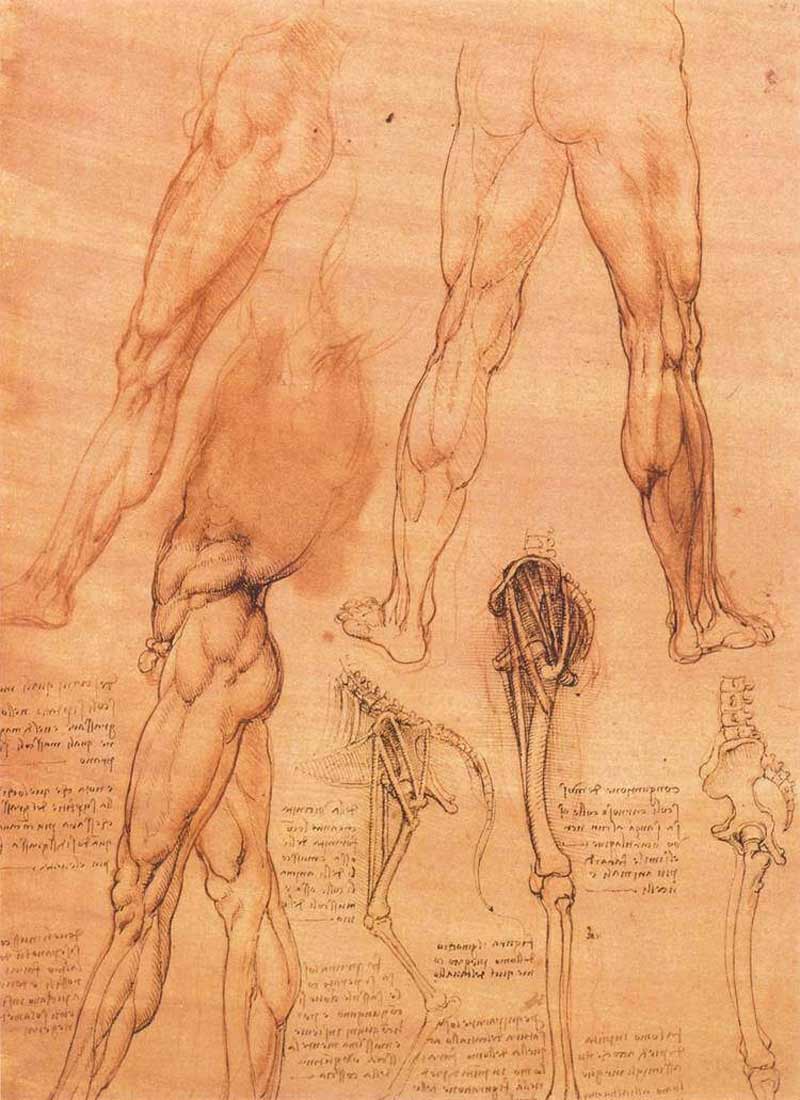

At some point in Leonardo's career- it is unknown exactly when- he began to perform dissections on dead bodies. His early dissections most likely took place in Milan, which, at the time, was a center of medical investigation. By the 1490s, his study of anatomy, which had originally started as artistic training, had developed into an independent area of research. He became fascinated by what he called the Figura istrumetale dell'omo, or the 'man's instrumental figure.' He sought to learn about and comprehend the human body's physical working as a creation of nature. For about two decades, he continued to do practical work in anatomy and dissections in Milan, and then at hospitals in Rome and Florence. According to his own accounts, he dissection thirty corpses in his lifetime.

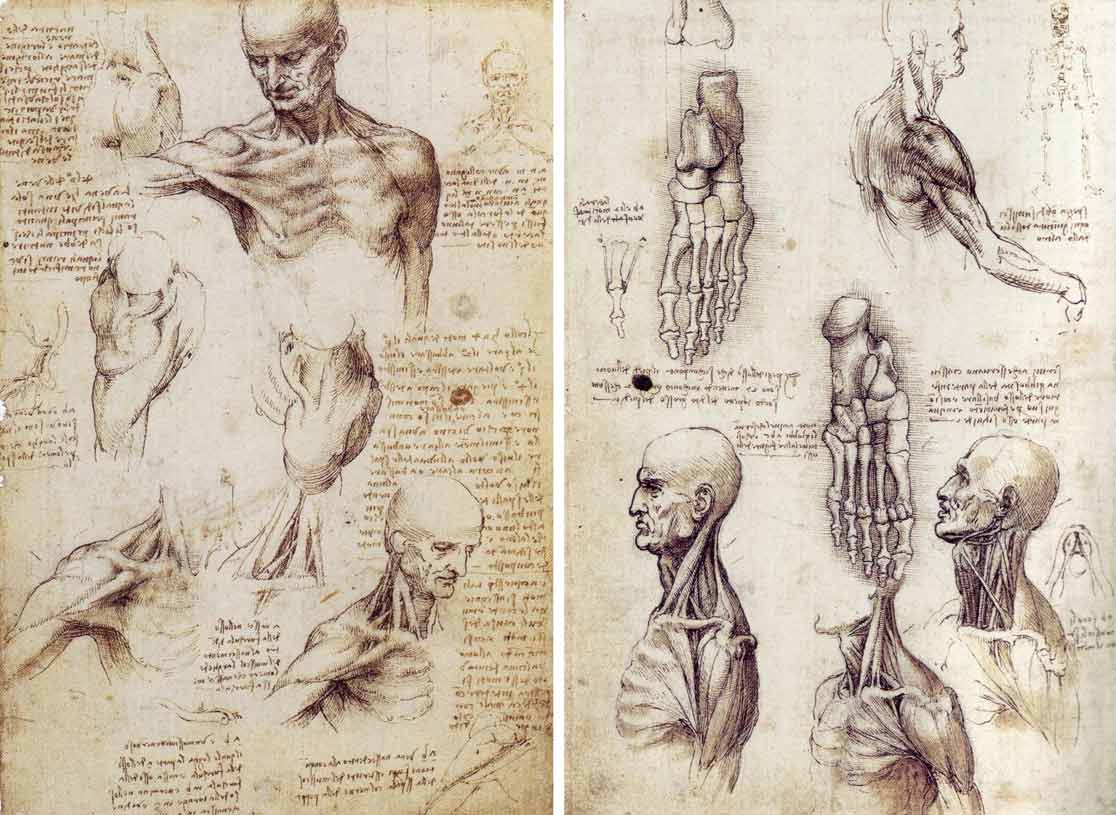

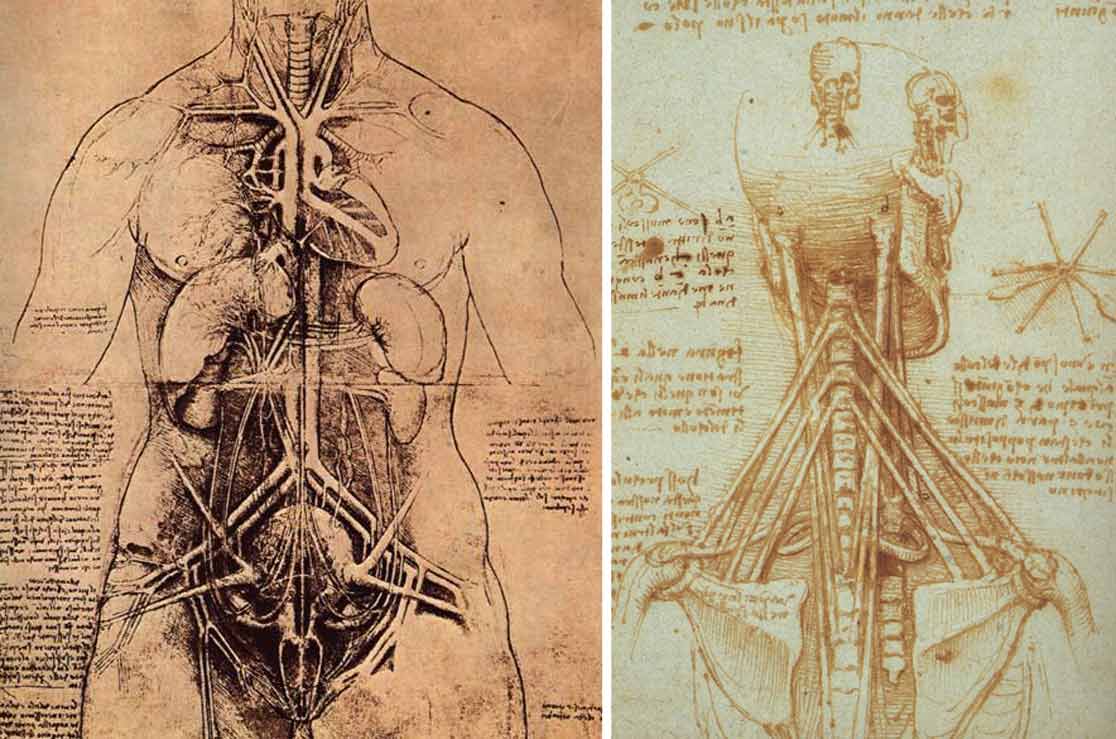

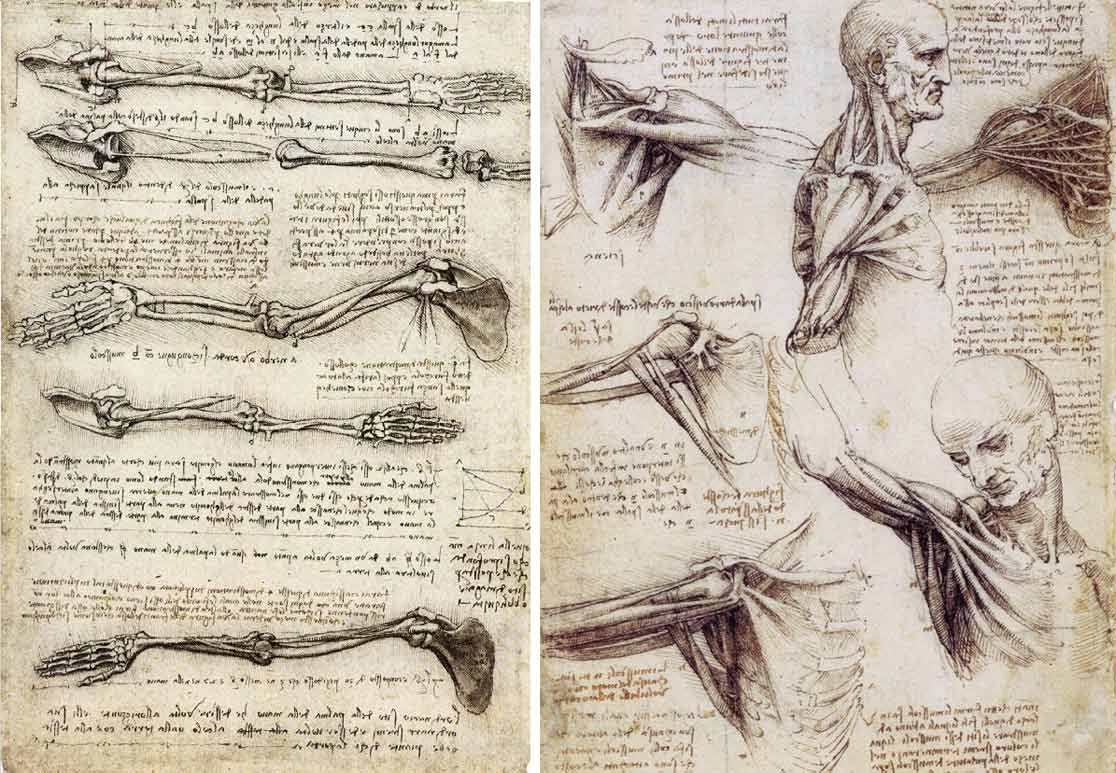

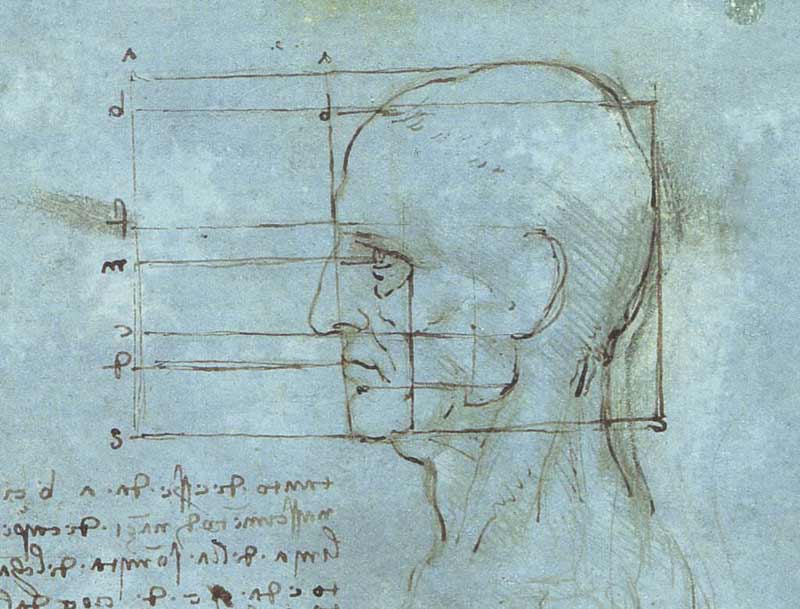

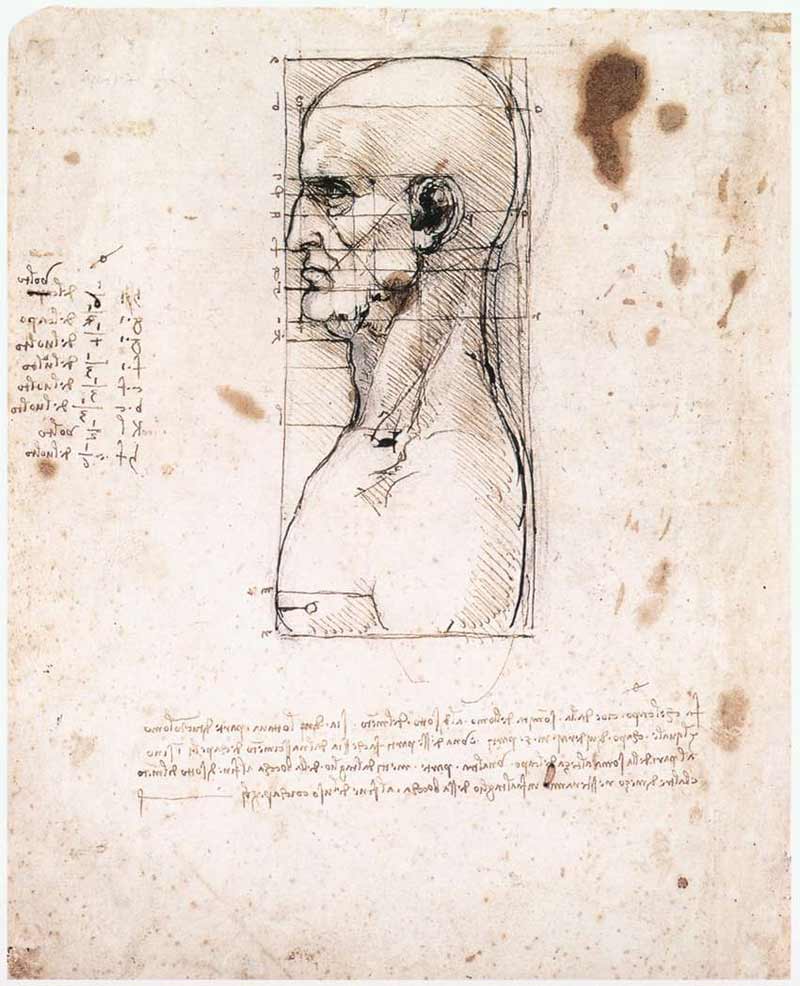

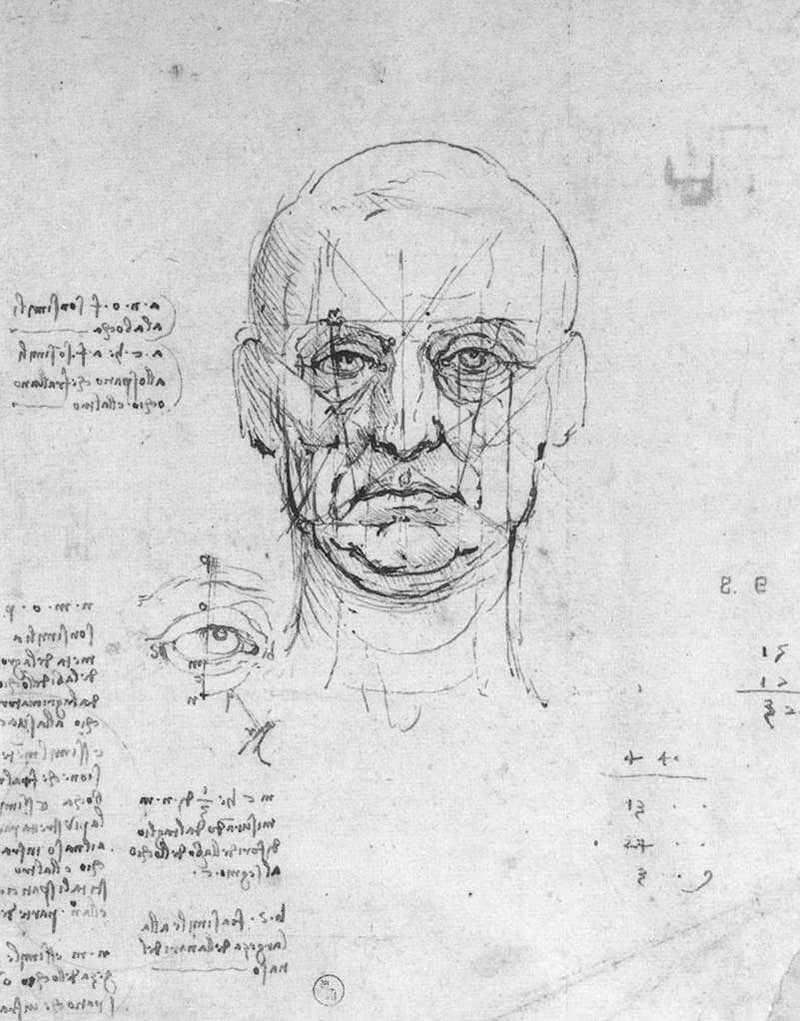

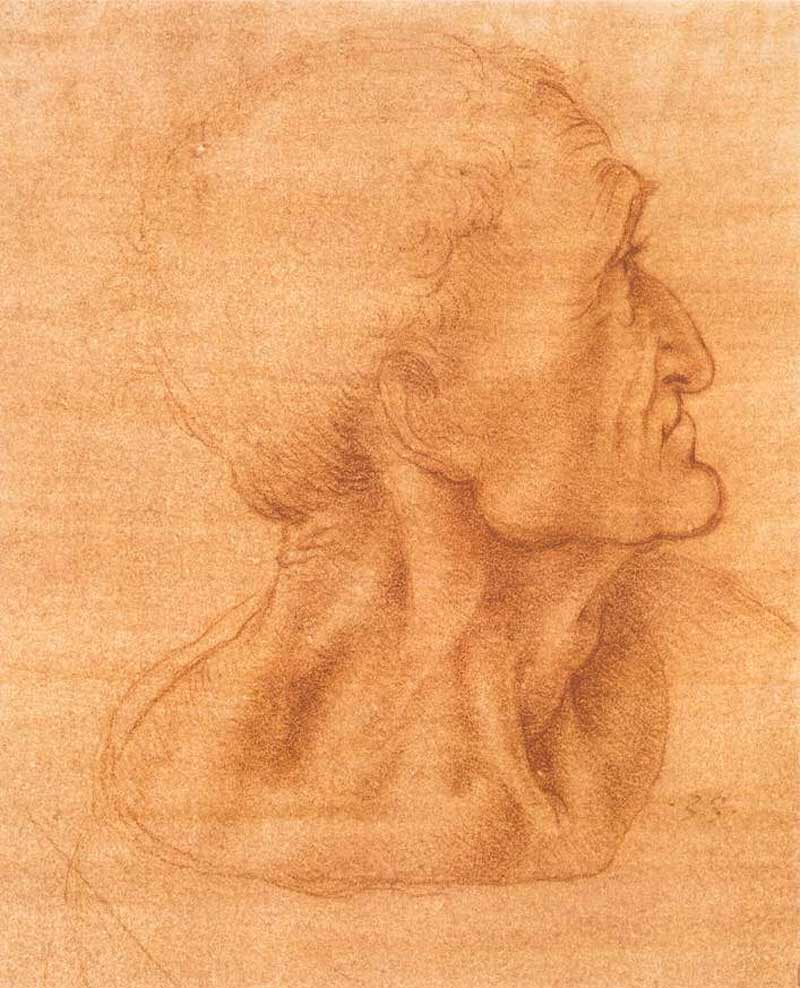

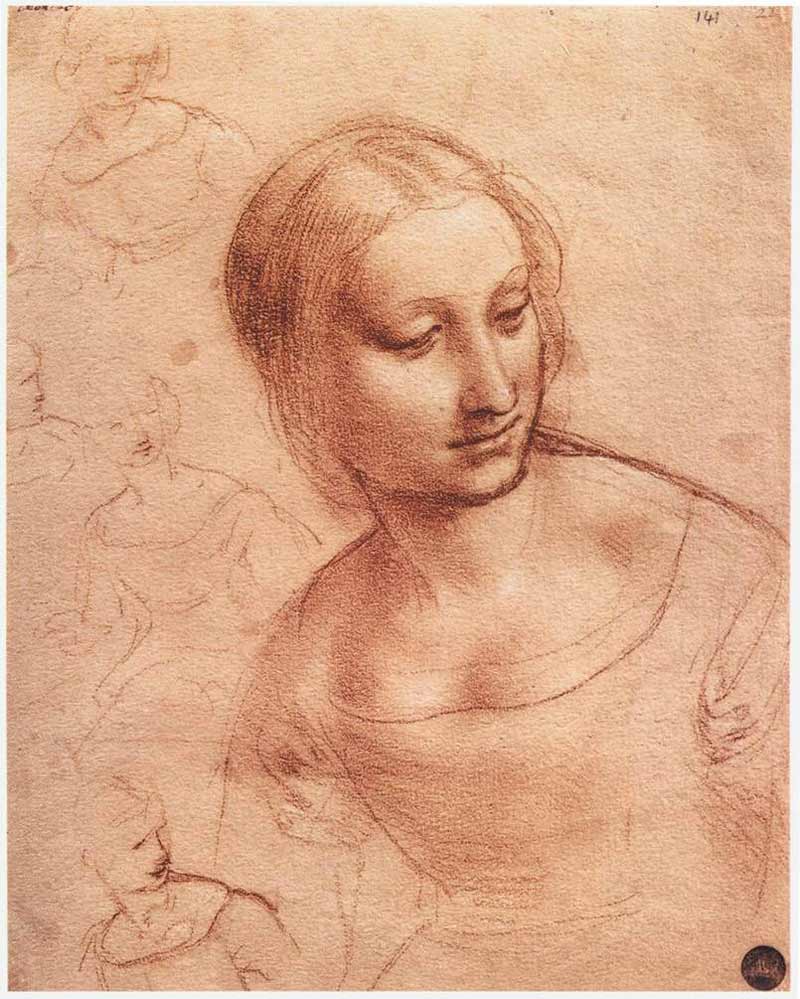

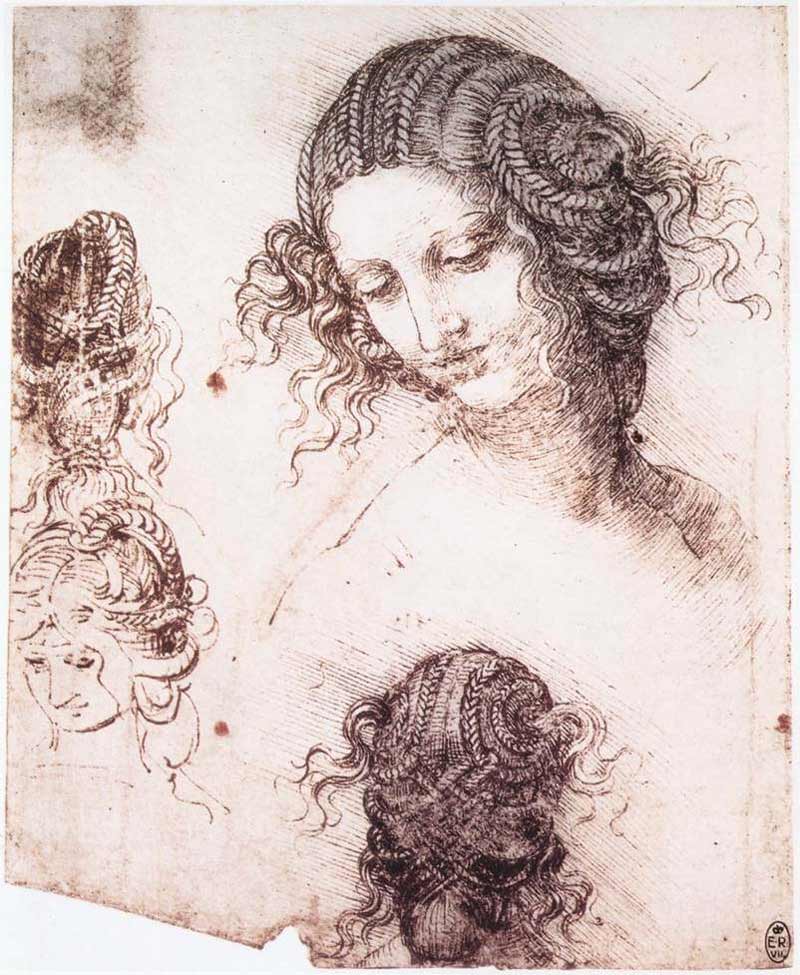

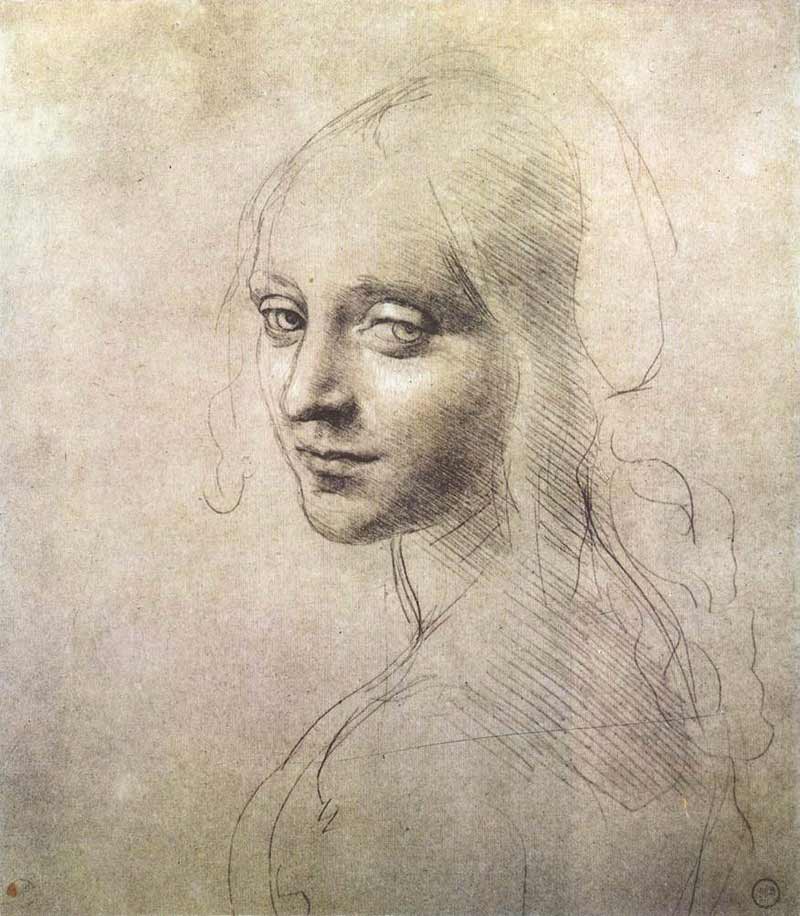

Leonardo's early anatomical studies focused primarily on the skeleton and the muscles, and he combined his anatomical study with physiological research. He observed and recorded the static structure of the body, and then proceeded to study the role of individual parts of the body in mechanical and dynamic activity. Finally, he studied and drew the body's internal organs, probing deeply into the brain, heart and lungs, which he considered the 'motors' of the senses and of life. He recorded all of his findings in anatomical drawings, which are among the most significant achievements of Renaissance science, and are based on a connection between natural and abstract representation. He depicted parts of the body in transparent layers that offer an insight into the organs by showing sections in perspective, reproducing muscles as stings, and indicating hidden parts by dotted lines. He even conducted drawings of a unborn child that he saw in the womb of a cadaver, making extensive notes on the position of the child within its mother's body, and drawing it from many different angles and perspectives. The value of these drawings lay in the way in which they synthesized many different experiences at the dissecting table, and made the data immediately and accurately visible to the viewer. He proudly noted that these drawings were often superior to descriptive words, however, during his lifetime he did share or publish his anatomical studies and life drawings, preferring to keep them hidden.

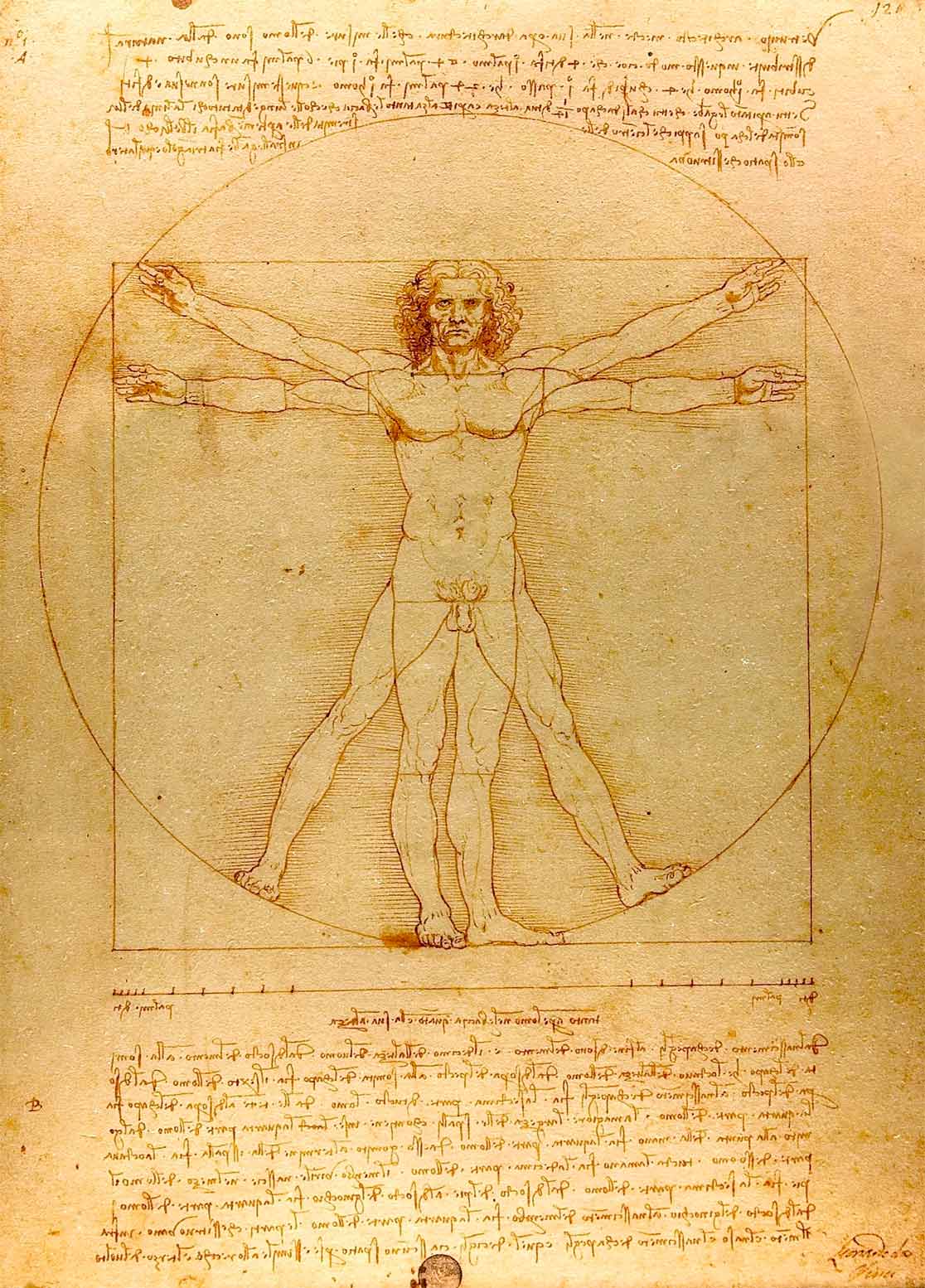

As well as drawing, Leonardo wrote extensively on the anatomy of the human body. Working with the mathematician Luca Pacioli, da Vinci investigated the proportional theories of Vitruvius, the first century BCE Roman architect, as presented in his treatise De architectura. Using the principles of geometry on the configuration of the body, Leonardo demonstrated that the ideal proportion of the human figure corresponds with the forms of the circle and the square. In his illustration of this theory, the so-called Vitruvian Man, Leonardo demonstrated that when standing firmly on the ground with outstretched arms, a human body can be contained within the four lines of a square, but when in a spread-eagle position, it can be inscribed in a circle. Leonardo also wrote extensively on the other proportions of the body, explaining that, for example, the head from forehead to chin is exactly one tenth of the total height of the body. Although Leonardo's Vitruvian Man was originally based on Vitruvius' writings, Leonardo took the theories much further than Vitruvius ever did. He continued to search for connections between the structure of the human body and other proportions in nature for the duration of his life.

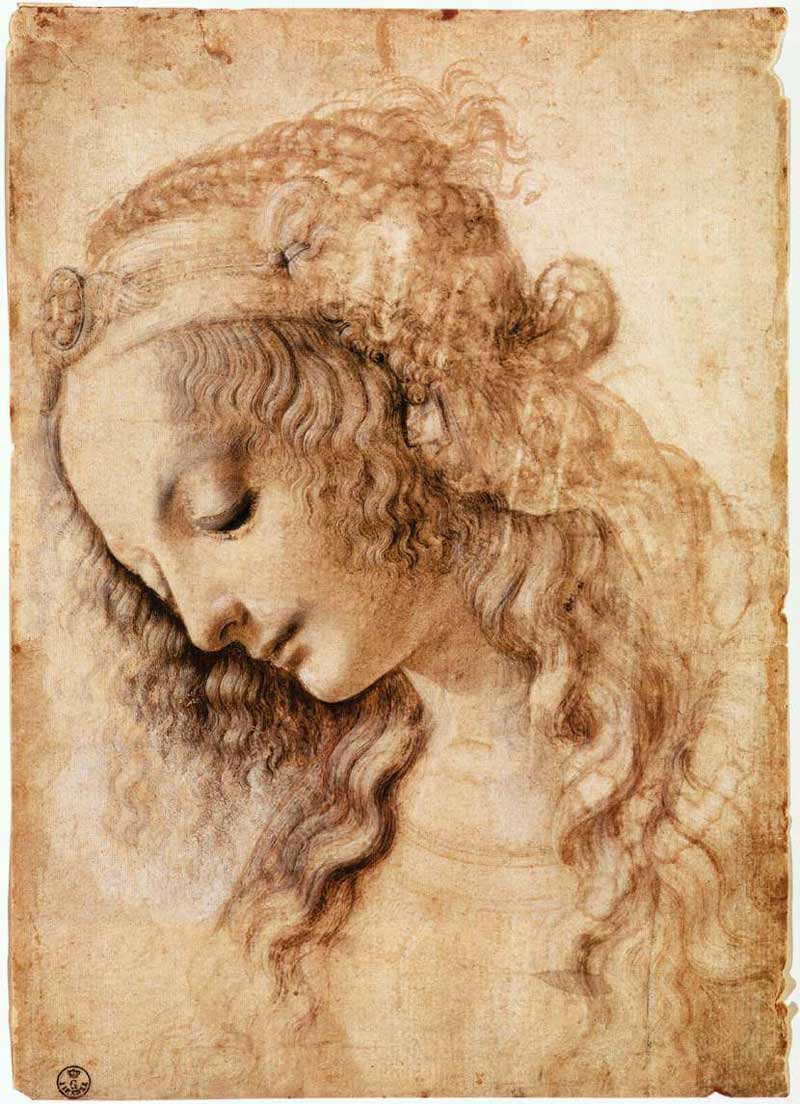

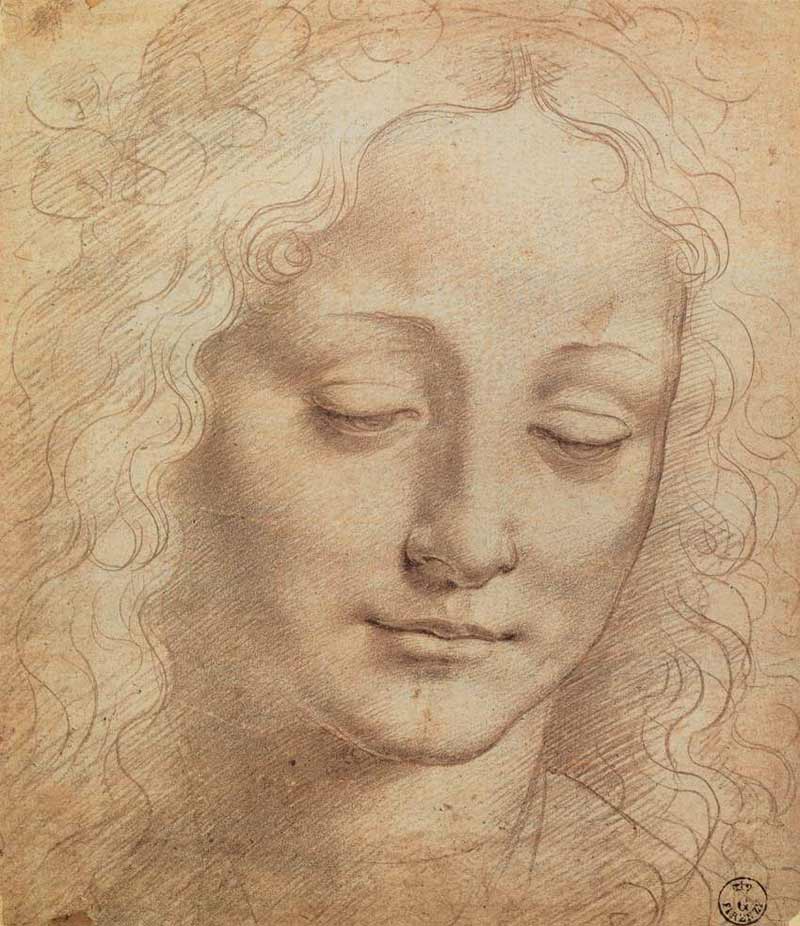

As well as drawings of dead bodies and internal organs, Leonardo also conducted many drawings and studies of living models, including his pupil and close friend Gian Giacomo Caprotti de Oreno, who often served as the model for Leonardo's life drawings. These drawings then often formed the foundation for many of Leonardo's most well-known and revered paintings.

References

- Jones, Jonathan, 'Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing review – the superhuman hits you like a thunderbolt,' The Guardian, January 31, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/31/leonardo-da-vinci-a-life-in-drawing-review-royal-collection-uk-museums

- 'Leonardo da Vinci,' Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leonardo-da-Vinci/Anatomical-studies-and-drawings

- 'Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing,' Manchester Art Gallery, http://manchesterartgallery.org/exhibitions-and-events/exhibition/leonardo-a-life-in-drawing/

- 'Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing,' Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/exhibitions/leonardo-da-vinci-a-life-in-drawing-0

- 'Vitruvian Man,' BBC Science and Nature, https://www.bbc.co.uk/science/leonardo/gallery/vitruvian.shtml

This is your unique chance to get a lifetime academy membership and a dedicated team of art teachers.

Such unlimited personal tutoring is not available anywhere else.