Michelangelo Buonarroti - The Great Renaissance Master

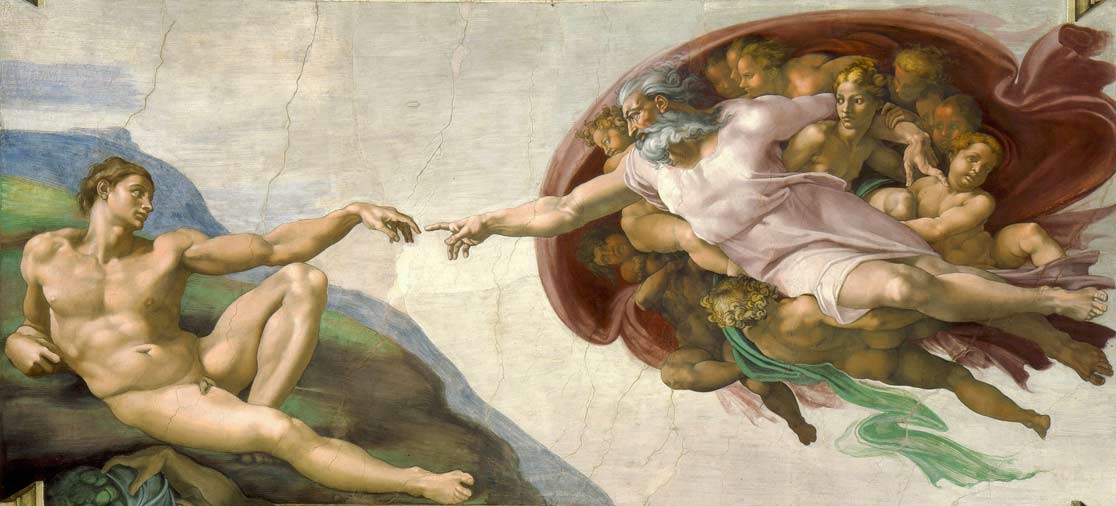

Michelangelo was an avid drawer throughout his life, using drawing as a way of testing and expressing his ideas for sculptures and paintings, as well as highly finished gifts or presentation drawings for his friends or admirers. While Michelangelo learnt a great deal about human anatomy from studying the idealized form of classical sculptures, he also relied heavily on life drawing to augment his knowledge of the body. He is most well-known for his large public works, such as the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and the sculpture of David in Florence. However, these works, with their carefully executed human bodies and extreme attention to anatomic detail, are the result of Michelangelo's great love of life drawing, and the hundreds of studies in which he meticulously noted down his observations of the human form and the effects of light and shadow on the body.

Michelangelo first learned to observe and draw the body when he entered the studio of the Ghirlandaio brothers in Florence when he was twelve. The Ghirlandaios placed drawing the centre of their practice, basing their large-scale frescoes on preliminary sketches that were then worked up to full size cartoons prior to executing the final painting. They would then be placed on the walls and ceilings where the finished work was to be situated, and the lines of the drawings pricked through to leave a guideline for the painter. It is thought that Michelangelo spent two years in this environment learning to draw. He went on to produce thousands of fine pen and chalk drawings which would later form the basis for his sculptures and frescoes.

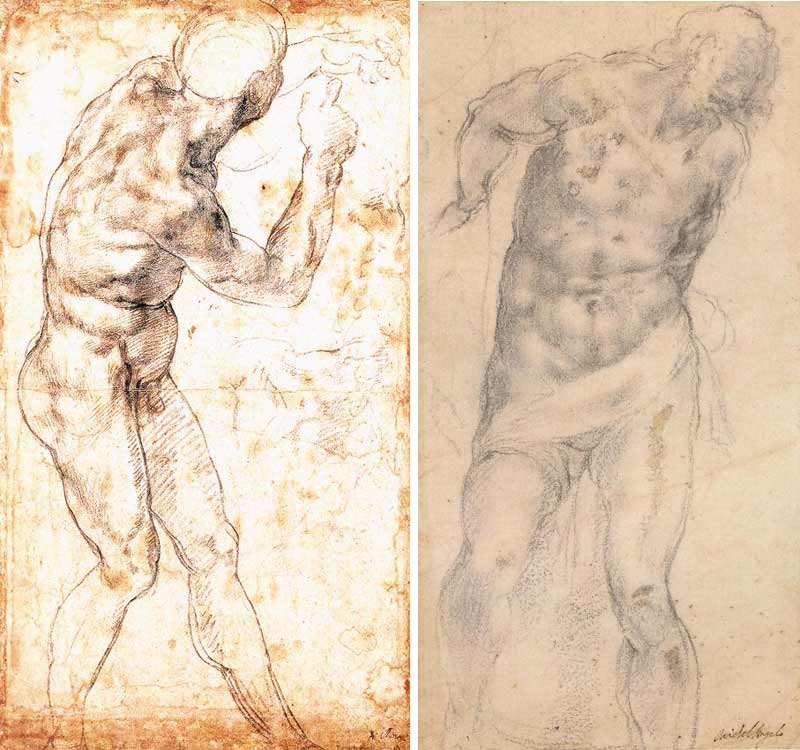

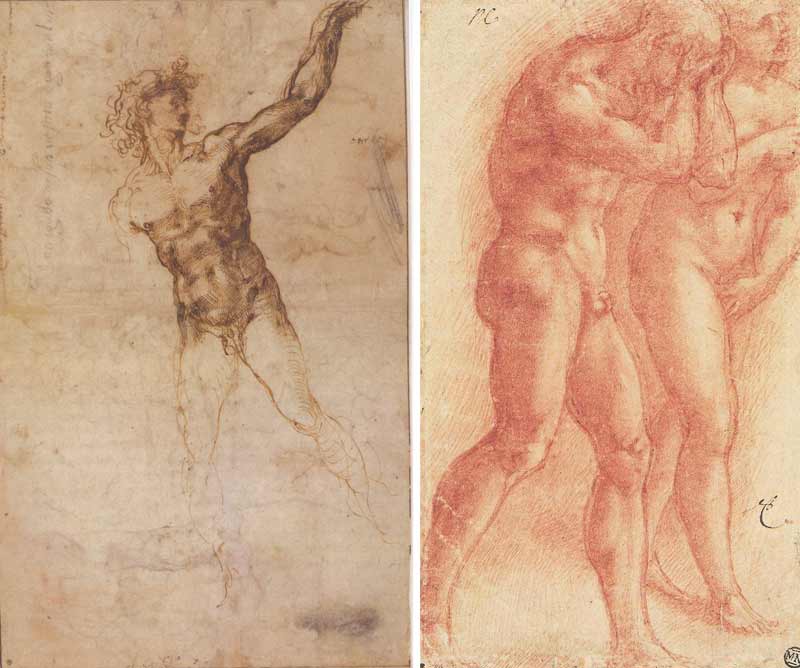

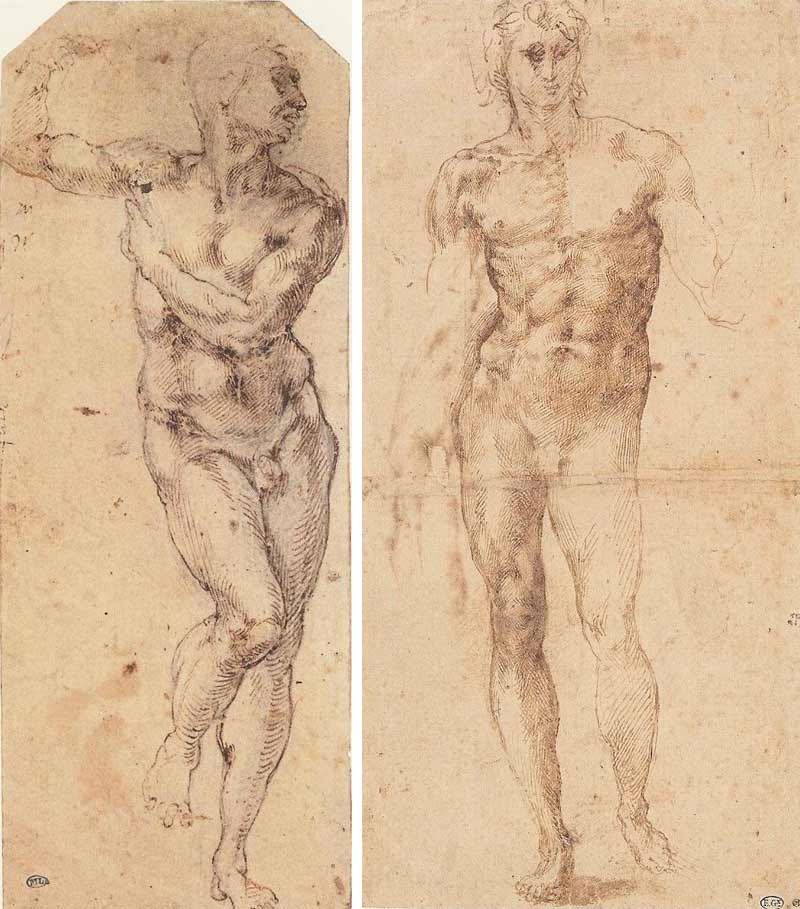

In his life drawing, Michelangelo concentrated on the naked male figure in a way that was relatively new to Western art. He carefully studied and recorded the structure of muscles and conveyed dramatic movement of the body. Many of his most recognizable and well-known works began as sketches on paper, and he used sketching and life drawing as a way to explore the best way to portray the narrative and formal qualities of his finished works.

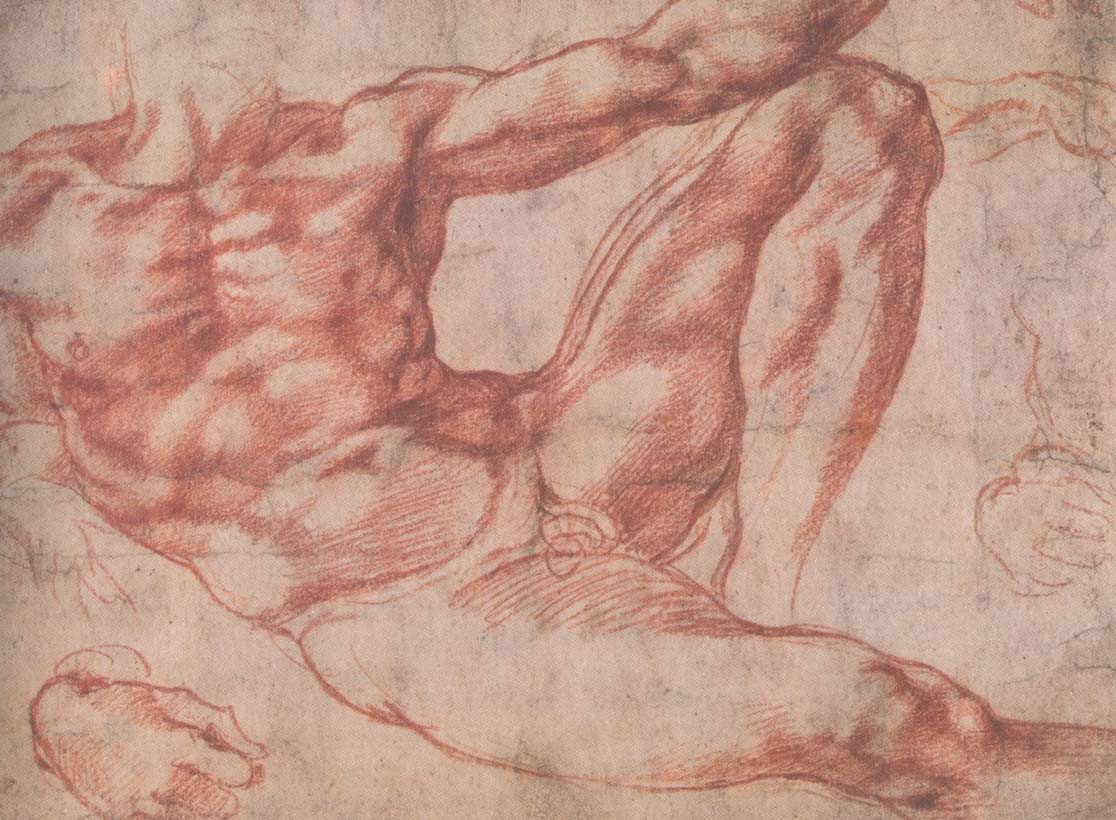

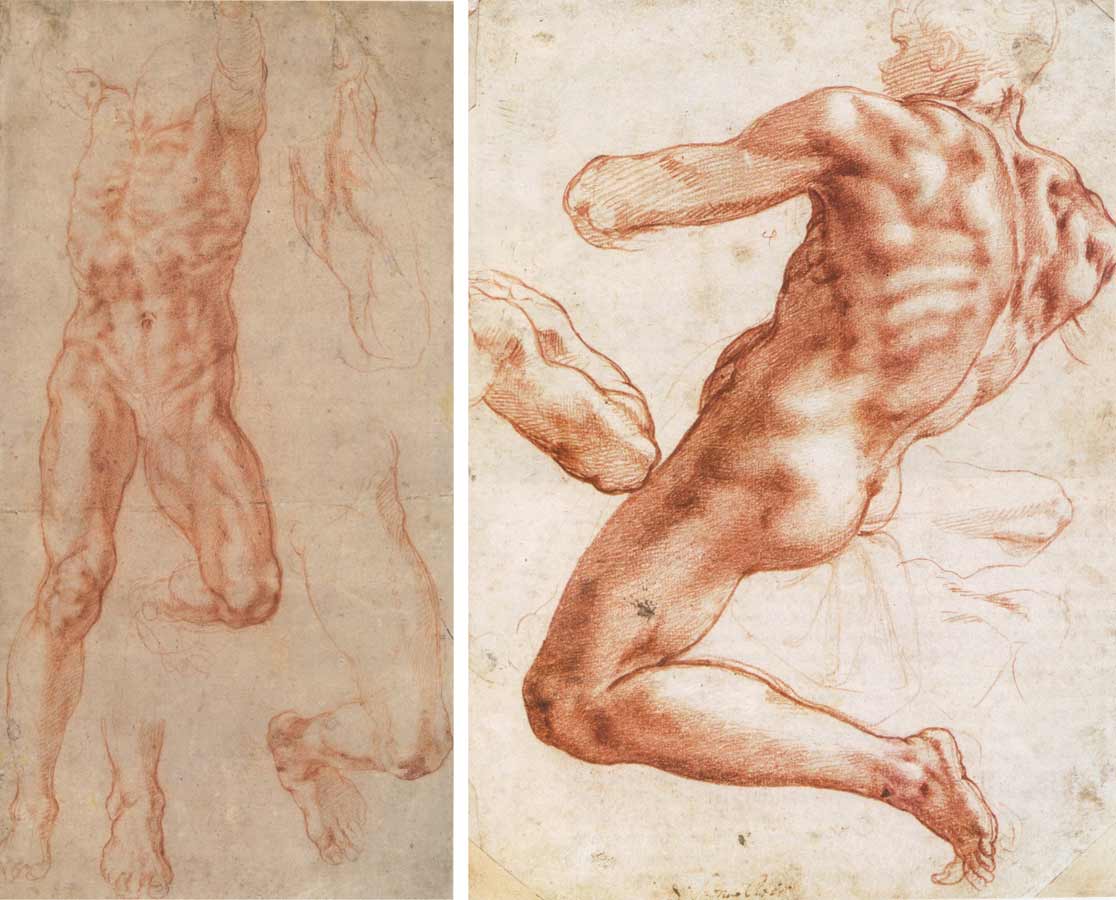

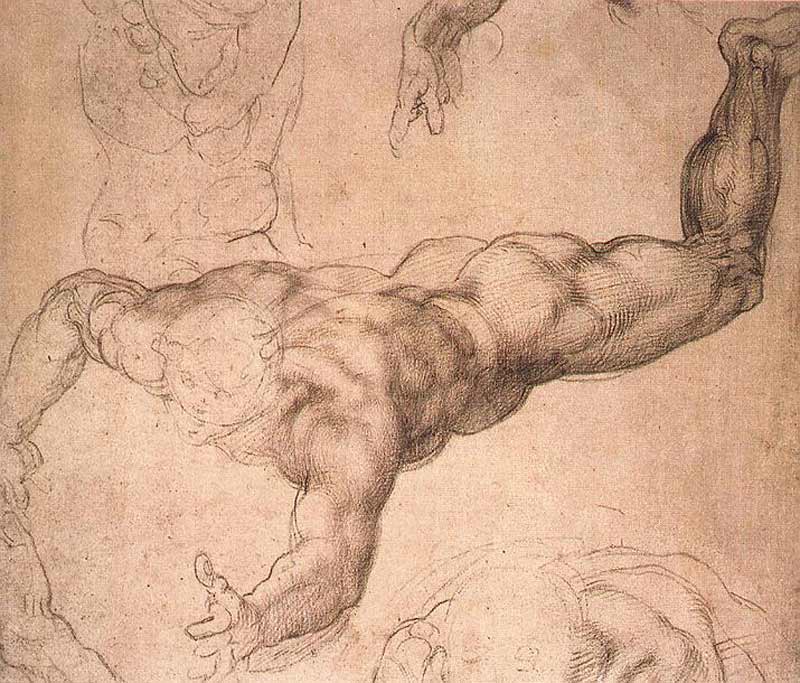

A red chalk drawing of a naked male figure, which bears resemblance to the figure of Adam from the Sistine Chapel ceiling, survives and is in the British Museum's collection. The drawing demonstrates how Michelangelo closely observed the human form while working out his ideas. He captures the musculature of Adam's torso with incredible detail, as well as the way light and shadows hit different parts of the body. There are repeated sketches of hands as he endeavored to find the perfect position and gesture before starting his painting. It is this intense observation of the human form, and the different shapes created by contracting and expanding muscles that make Michelangelo's works so unique and memorable, even hundreds of years after his death.

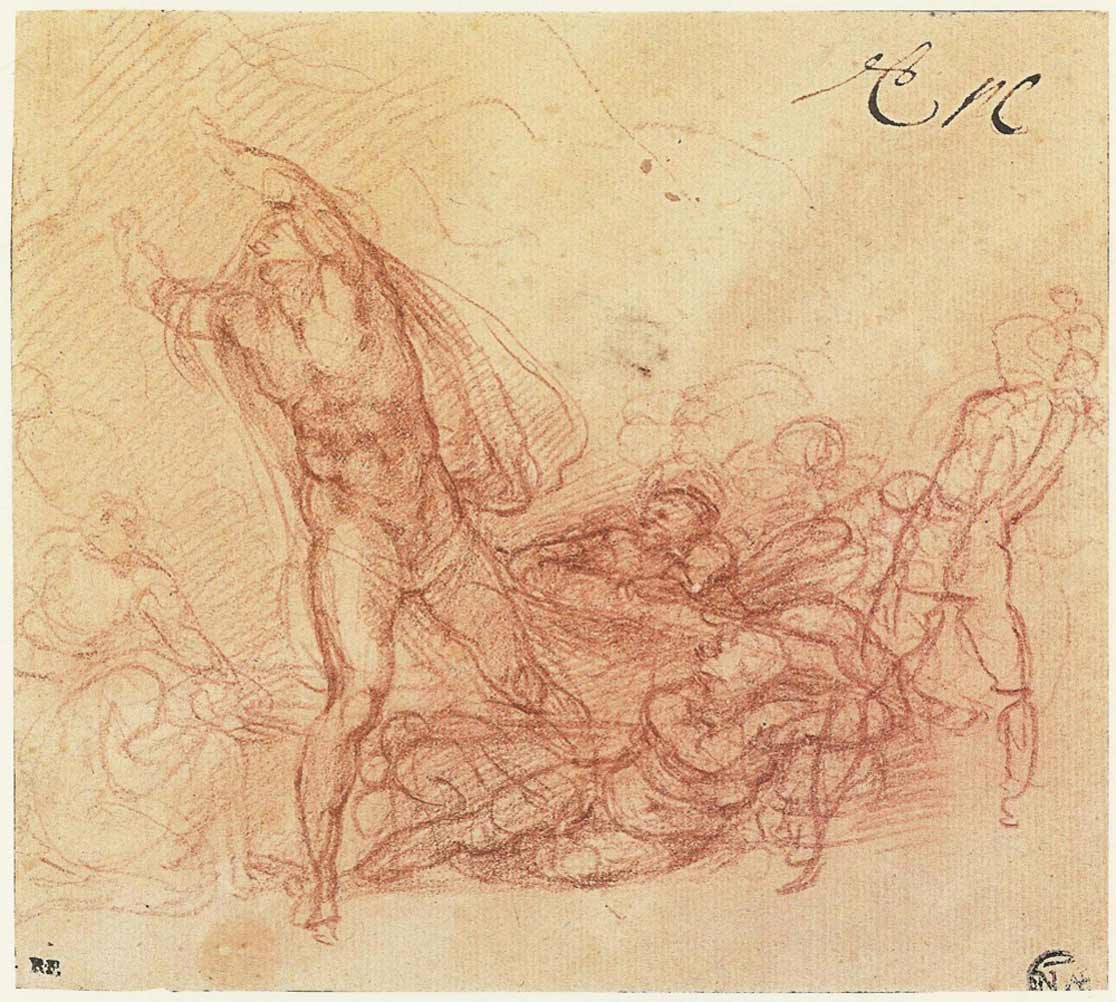

While Michelangelo's sketch for the figure of Adam was just a preliminary drawing, he also created many so-called 'presentation drawings,' which he considered works of art in their own right. One of these surviving presentation drawings, inspired by Ovid's Metamorphoses, depicts the mythological giant Tityus. Tityus was punished for attempting to rape Lato, the mother of Apollo and Diana, with eternal torment by being chained to a rock in Hades. Every day a vulture would rip out his liver, the seat of lust, and each night the liver would regrow, only to be ripped out again the next day. The drawing shows the vulture hovering over Tityus' body, in the moment before his beak pierces Tityus' skin.

Michelangelo's fascination with the human body is evident in the way he has captured the musculature of Tityus' as yet undamaged torso as he twists away from the vulture.

Interestingly, his position is similar to that of Adam's in the Sistine Chapel preparatory sketch: both men are shown reclining with the front leg outstretched and the back leg bent with a raised knee. While ostensibly a drawing of a mythological scene, this work really serves to highlight how fascinated Michelangelo was with accurately observing and drawing the human form.

Michelangelo was fiercely protective of the studies and drawings he produced as preparatory sketches for his paintings and sculptures. He was very paranoid about where his drawings would end up, and the threat of plagiarism, and was therefore guarded about his works. He kept a firm watch on where his drawings ended up, sending many of them home to his family, and is it thought that he burnt thousands of drawings before his death as a way of protecting his ideas from his competitors. There are around six hundred drawings by Michelangelo still in existence, which demonstrate how closely he adhered to the natural world in the creation of his most famous images.

References

- Caistor, Nicholas, 'Michelangelo and the art of drawing,' BBC News, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/4836252.stm

- Esposito, Maria and Christian, John, 'Michelangelo to Matisse—Drawing the figure: A look at 500 years of figure drawing', World Socialist Web Site, April 17, 2000, https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2000/04/mich-a17.html

- Hall, James, 'Michelangelo and the mastery of drawing,' The Guardian, March 6, 2000, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/mar/06/michelangelo-dream-drawing-courtauld-exhibition

- 'Recto: The punishment of Tityus,' Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/912771/recto-the-punishment-of-tityus-verso-the-risen-christ

- 'Drawing- Creation of Adam,' British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=200159001&objectId=716122&partId=1#more-views

- 'Work in Focus: Michelangelo's drawings – Tityus,' Royal Academy, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/event/work-in-focus-michelangelos-tityus-drawings-art-history

This is your unique chance to get a lifetime academy membership and a dedicated team of art teachers.

Such unlimited personal tutoring is not available anywhere else.