Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino - The Great Renaissance Artist

Raphael is often considered the third great artist of the Renaissance, following Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, his predecessors of only a few years. In what was a very short life, even by contemporary standards- he died age thirty-seven- he was prolific, and left behind a large collection of both painted works and drawings. Like Michelangelo and Leonardo, drawing constituted a large and important part of Raphael's oeuvre. His contribution to the art of drawing was significant, and he successfully mastered many techniques and media, including metalpoint, chalk and pen and ink. It is in his drawings that Raphael's most spontaneous creativity is demonstrated, and the subjects he chose to depict in his drawings demonstrate his interests and pleasures more so than any of his paintings. Even when he had a workshop that amassed fifty assistants, many of whom completed his paintings or parts of his paintings, he always executed his drawings and studies with his own hand.

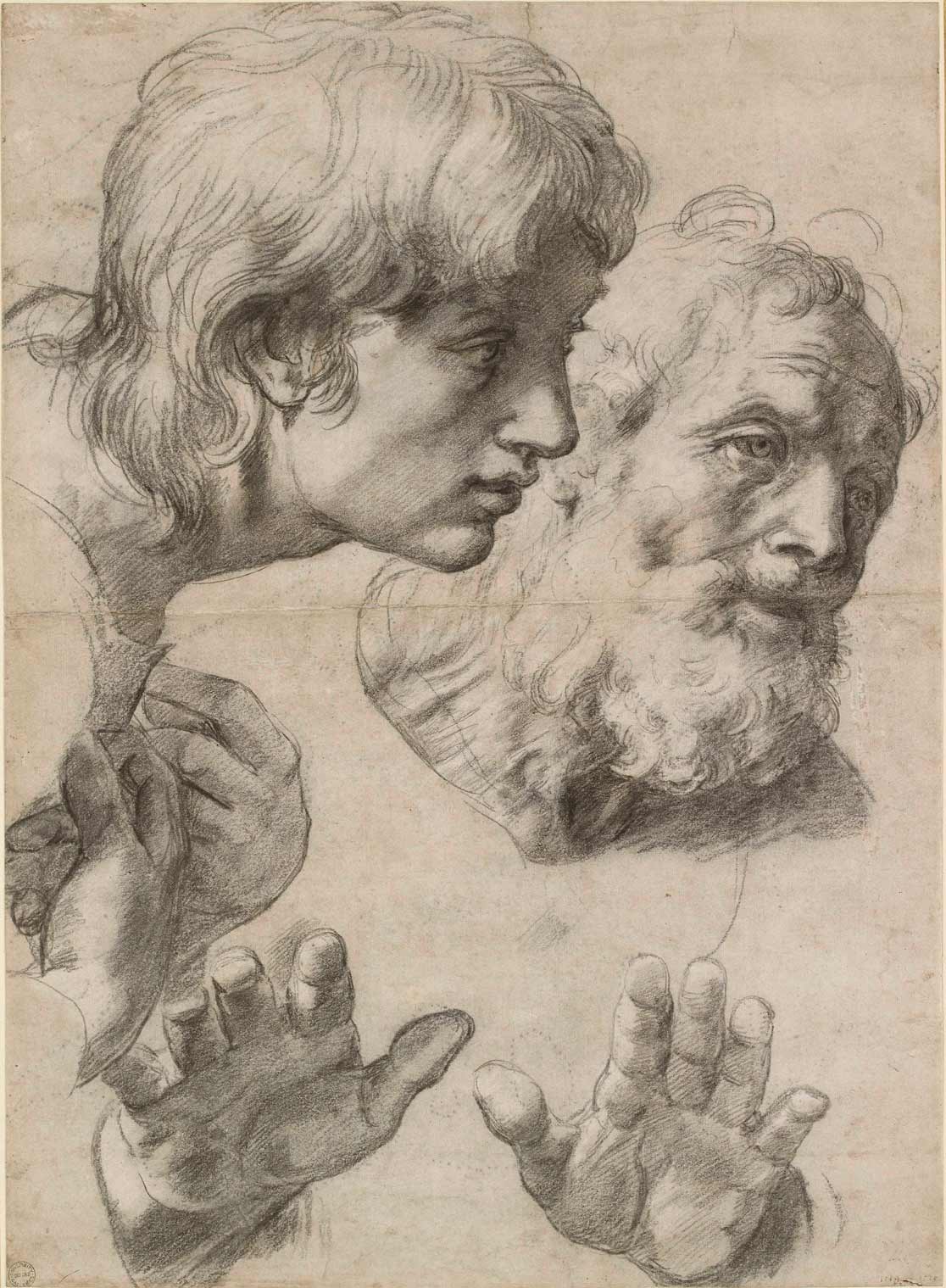

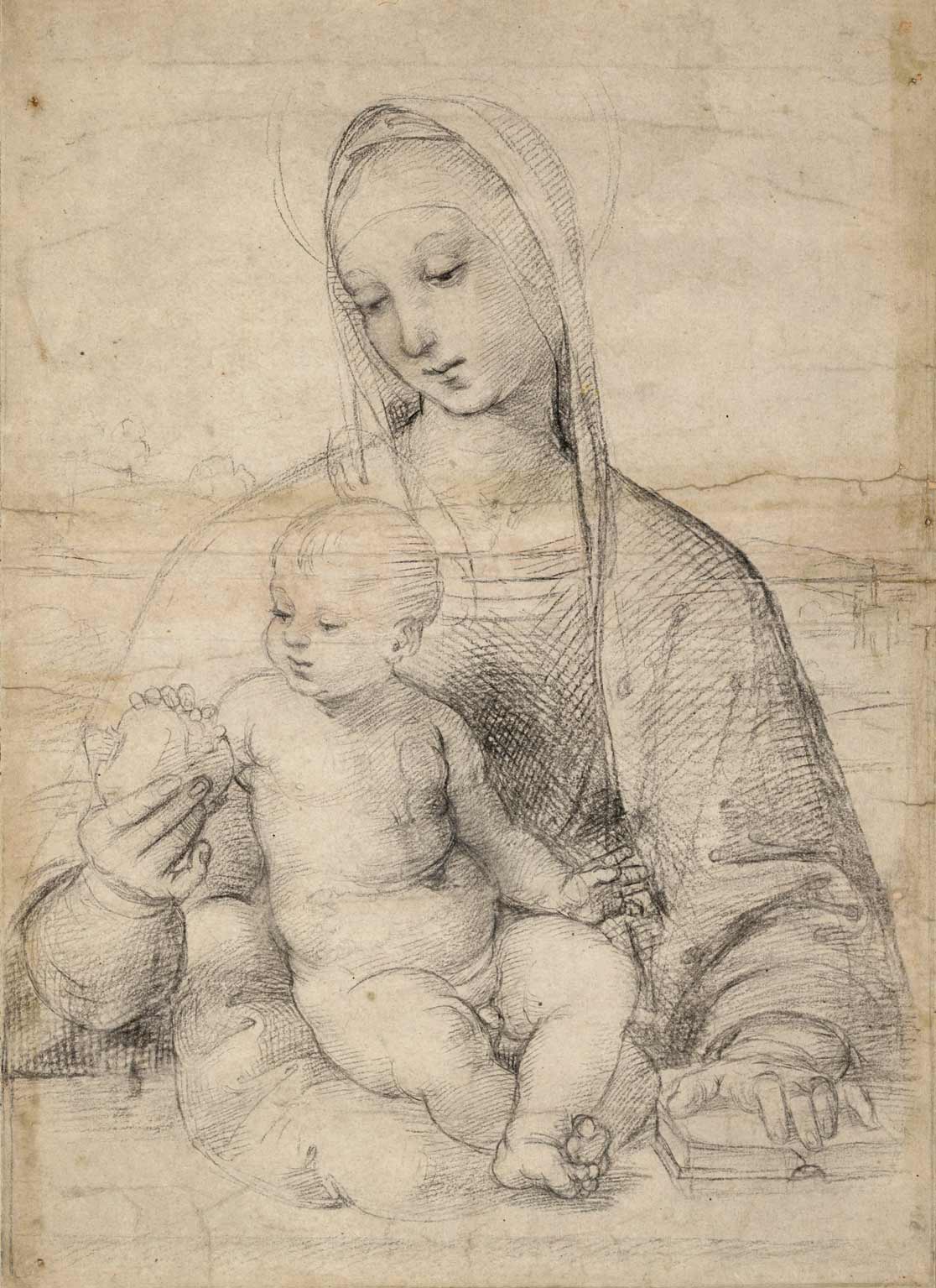

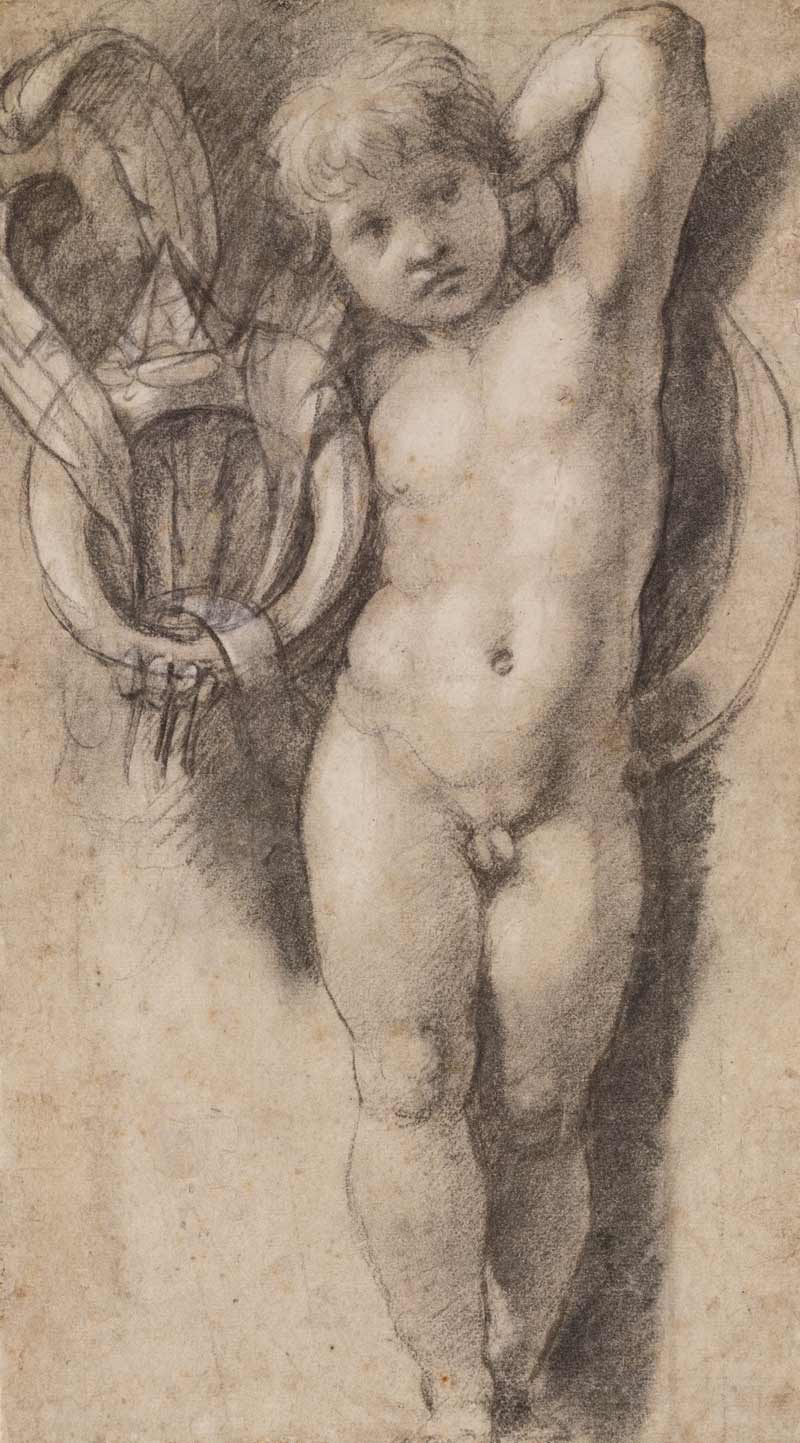

Raphael used drawing extensively as a tool for brainstorming, and for experimenting with a wide variety of styles and techniques. His methods varied from stabbing a pencil to scratching metalpoint to gently shading chalk, and he trialed how the combination of these different media could produce different visual and emotional results within his drawings. Raphael used drawing as a way to attempt to discover the more expressive forms he can, and it is clear from the huge variety of his work that he believed experimenting with different media and drawing would allow him to do this. He often returned to the same subject many times, for example the common trope of Madonna and Child, in order to depict it with the most drama and emotional potency. In one such work, he uses black chalk, to create a sparsely linear image; in other, he uses the same medium, but in a completely different way, employing heavy shading and white highlight to create an image that is much more darkly emotional and tender. His line is exact yet tender, and he is able to communicate an often emotional or sensitive subject with both precision and delicacy. While some of his drawings clearly show him trying to figure out the composition and align the figures in his pictorial space, many of them demonstrate his interest in and desire to capture the body and human emotions as naturalistically as possible.

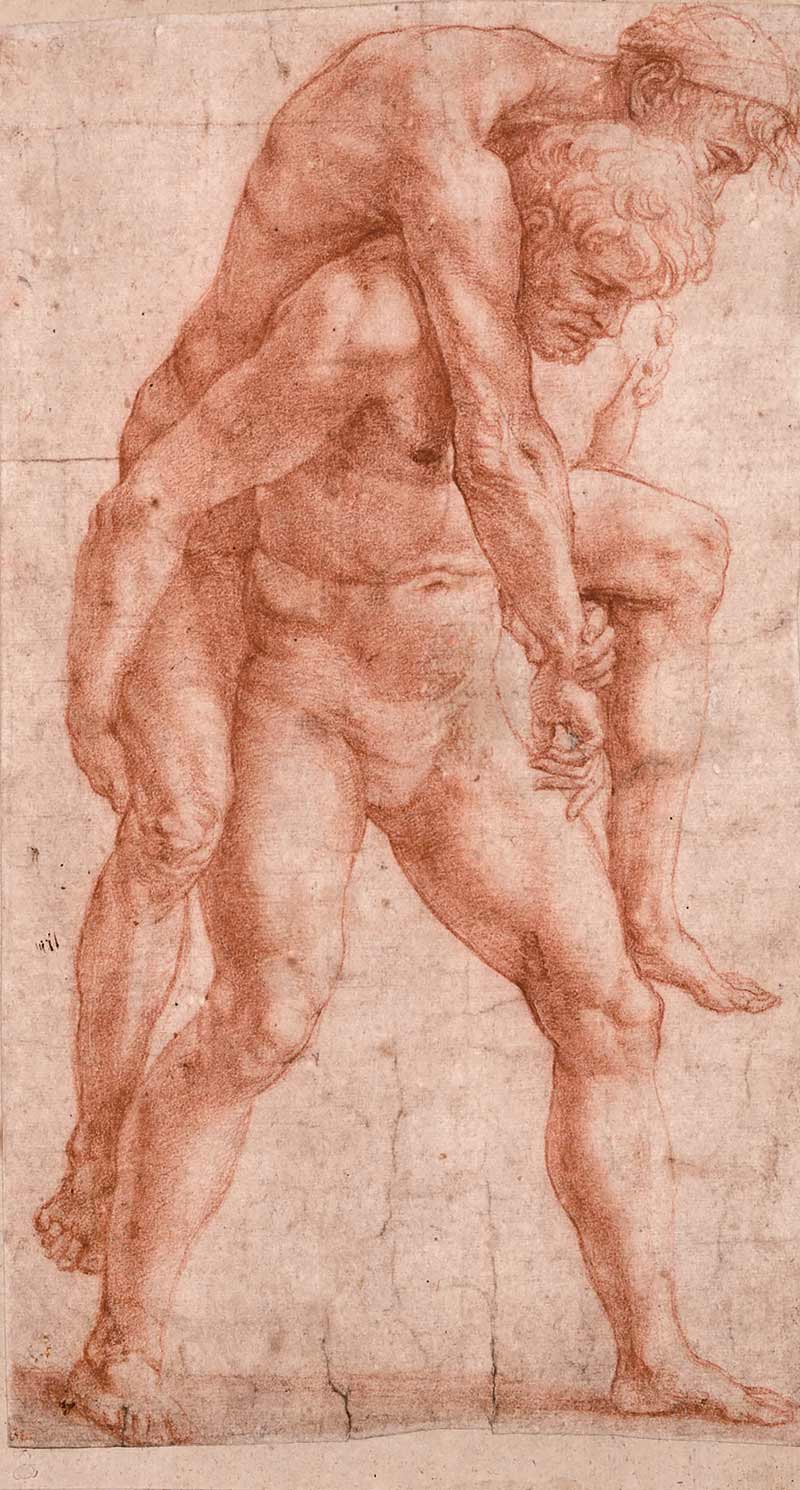

In his drawings, Raphael often captures the human body in unusual positions or moments of dynamism, sitting uncomfortably on a rock, for example, or carrying another man on his back, straining under the weight of another body. He is clearly interested in the movement of bodies, and how they look performing actions that may not always appear in paintings. Many of his sheets feature the same body part or gesture repeated as he attempts to capture it in the most impactful and realistic way. Studies of hands and outstretched arms appear alongside expressive faces.

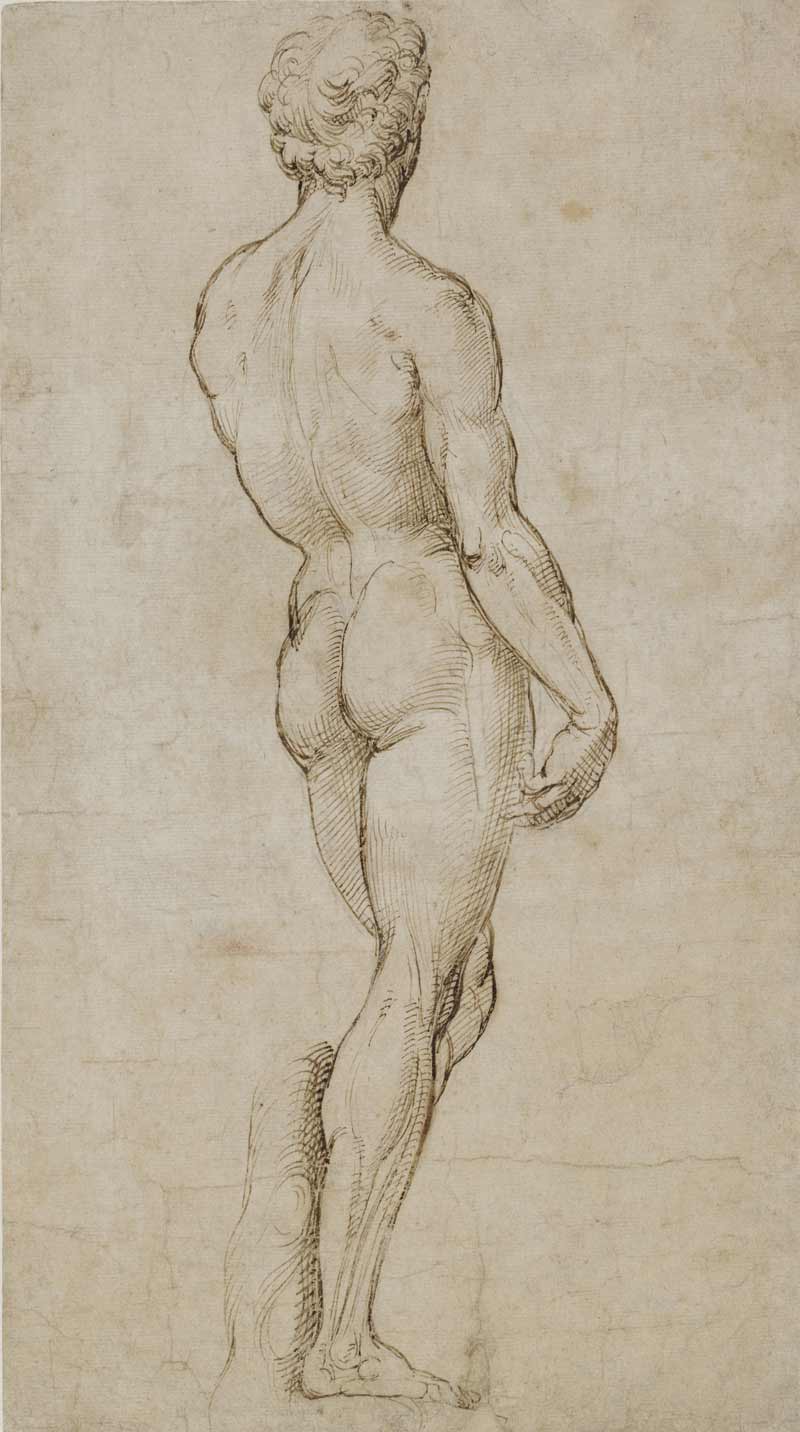

As well as drawing from life, Raphael also created many drawings in which he used sculptures as his models; Michelangelo's David, for example. There are two existing drawings by Raphael which seem to refer to or mimic David, one in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the other in the British Museum. Interestingly, art historians and scholars have assessed these drawings, particularly the pose of the model, which diverges slightly from Michelangelo's sculpture. In the sculpture, David's left arm is folded and his hand rests near his shoulder. In Raphael's drawing, however, the left arm is outstretched. Scholars have attributed this change to the fact that Raphael probably did not copy the pose from the sculpture itself, but rather used the sculpture as a starting point, before drawing from a life model. It is also probably that he drew on poses of other classical and antique sculptures for additional inspiration, but most likely worked directly from life when executing the actual drawing. Even when drawing inspiration from the work of older artists, or indeed sculptures from antiquity, Raphael still opted to use a live model, and draw on the real human body as opposed to one of stone. In other drawings, including a study of three men, also in the British Museum, Raphael employs the same, classical contrapposto pose from different angles, in order to explore the different movements and gestures of the human body.

Many of Raphael's drawings are cartoons or preparatory sketches for paintings, as is demonstrated by the fact that many are covered with many small holes. Either the artist or an assistant would prick the outlines of the figures with a sharp object, and then bang a bag of charcoal dust over the drawing, so that the black dust passed through the holes onto the other surface below. The artist then had an outline in charcoal dots on the surface below, which he could the join together to form the image.

References

- Jones, Jonathan, 'Raphael: The Drawings review- magnificent, mind-opening exhibition,' The Guardian, May 30, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/may/30/raphael-the-drawings-review-a-magnificent-mind-opening-exhibition

- Kwakkelstein, Michael W, 'The Model's Pose: Raphael's Early Use of Antique and Italian Art,' Artibus Et Historiae 23, no. 46, 2002, pp 37-60

- Neuendorf, Henri, Forget His Paintings, Raphael's Drawings Reveal His True Genius, Artnet, June 14, 2017, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/raphael-drawings-ashmolean-991430

- Waters, Florence, 'A once-in-a-lifetime glimpse inside Raphael's creative process,' Christie's, July 18, 2017, https://www.christies.com/features/Raphael-The-Drawings-8368-1.aspx

- 'Raphael,' The Art Story, https://www.theartstory.org/artist-raphael-life-and-legacy.htm

This is your unique chance to get a lifetime academy membership and a dedicated team of art teachers.

Such unlimited personal tutoring is not available anywhere else.