How to Draw a Person

This is your unique chance to get unlimited personal tutoring at a tiny fraction of what it really costs.

Don't miss your once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

Enroll in the Life Drawing Academy now!

How to Draw a Person

By Alexander Ryzhkin

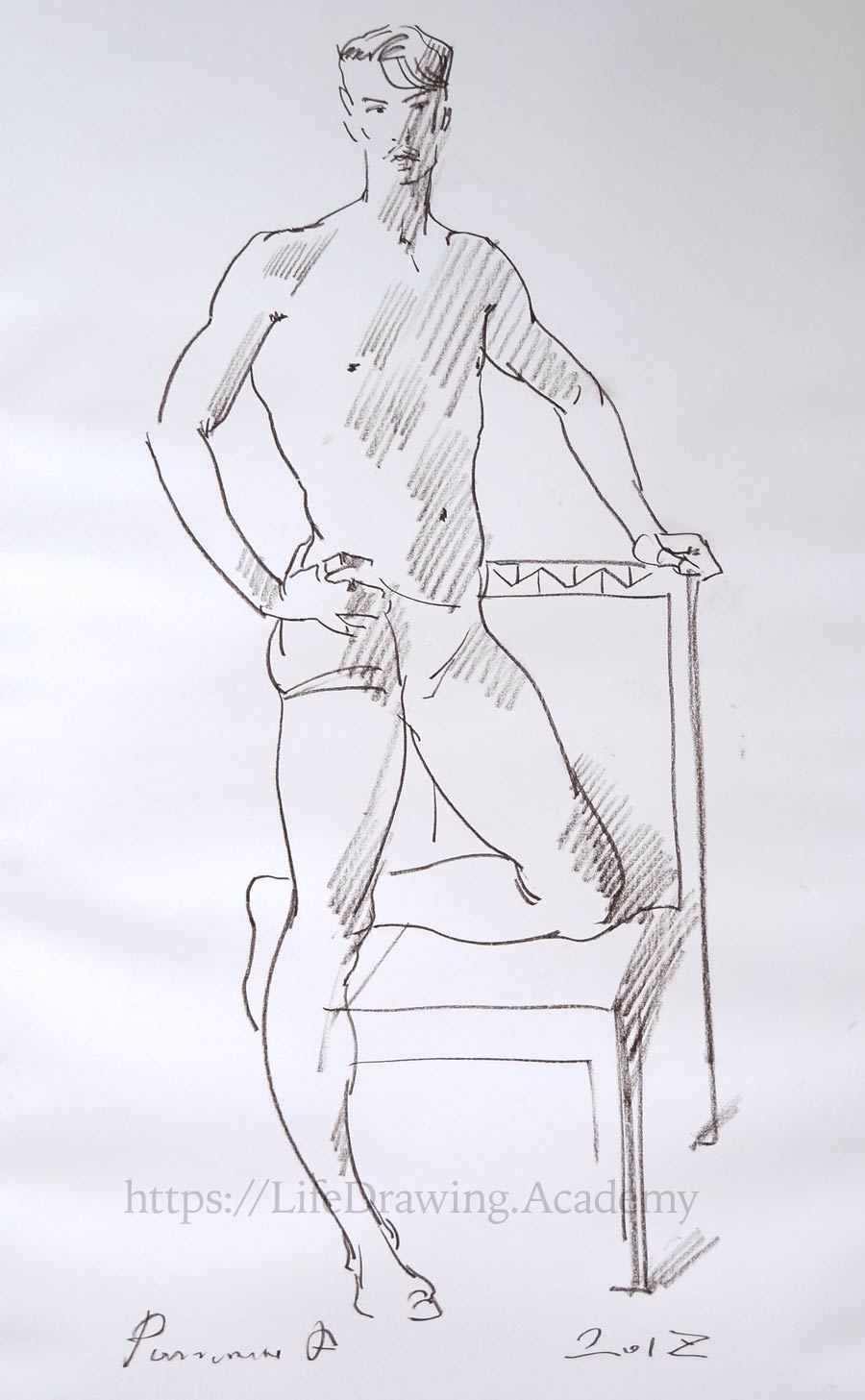

In this video lesson, you will discover How to Draw a Person Easy. I will show how to make a fast life gesture sketch of a standing figure.

Let's begin. When you have sufficient drawing skills and have a good feeling for the paper size, you can do gesture sketching by judging proportions by eye without measuring proportions and sizes with a pencil and without making corrections with an eraser. I know that the model's head fits about eight times into the figure's height, and I do a sketch in full strength from the very first strokes. Likeness of a portrait is optional in such sketches. You may have another creative task, for example choosing and studying a pose for a future composition.

There are many styles of sketching. None of these styles can be considered the only right way of fast drawing by an artist. In fact, there is no right or wrong way of gesture drawing—what works for one artist might not work for another. This is a matter of personal preference, habits, and education. Do not worry if some proportions are slightly off, and do not waste precious time erasing and redrawing when you have only few minutes per pose. What is important in such sketching is drawing what you know instead of copying what you see.

As an art teacher, I have seen many beginners who struggle with fast gesture drawing because they lack the necessary knowledge of human anatomy and proportions. When I sketch, applying the proportions of a human body happens on autopilot, almost subconsciously. For example, I know that the line of the eyes divides the head exactly in the middle. This is what I apply in drawing without even measuring this proportion on a model. I know that the width of the shoulders in a male figure is about three times the width of the head. I apply this knowledge automatically in my sketch. I know that the elbow is about at the same level as the end of the ribcage, so I can use this knowledge to check the correctness of alignments in my drawing, and so on.

Drawing happens not on paper, but in the artist's head. This is a cognitive process of analyzing visual information and constantly solving a chain of questions in my mind. Such questions may include the following:

- Which is greater—the height of the head or the distance from the breast line to the navel?

- Which is bigger—the height of the head or the width of the waist?

- Does the deltoid in my drawing point to the middle of the upper arm?

- Is the figure in my drawing symmetrical?

- How does the point of insertion of the chest muscle influence the chest contours?

- What is the alignment of the edge of the shoulder, the nipple, and the navel?

- What is the tilt of model's shoulders?

- Does the middle of the figure coincide with the pubic bone, and is it slightly higher than the middle of the paper?

- And so on.

As long as I ask and solve such questions in my mind during sketching, I'm drawing what I know. As soon as an artist stops thinking that way, he or she stops drawing constructively and starts copying what one sees, which results in drawing mistakes. What you see in this sketch are just few outlines. However, every line is done not just because I see it that way, but because I know what creates its shape. For example, the outline of the leg is drawn as you see it because I know how it is shaped by the quadriceps, how the construction of the knee joint influences its shape, how the calf muscle plays its role in the volumes of the leg. I also constantly compare proportions of different parts of the body to each other. For example, when drawing a knee, I look at the neck and compare its width to the knee, both on the model and in my drawing. Such cognitive drawing comes as a result of long practice.

Rendering tonal values in such short sketching is optional. I have some time left and can mark the main shadows of the figure. However, if your speed of drawing is slower, you may want to have another creative task—for example, working on the main proportions of a human body rather than describing its shape in tones. As you see, I'm using a "candle" grip on the pencil, which allows me to stand farther from the drawing board and gives me freedom to apply longer strokes...

[ The full lesson is avaibale to Life Drawing Academy members ]

This is your unique chance to get a lifetime academy membership and a dedicated team of art teachers.

Such unlimited personal tutoring is not available anywhere else.