How to Draw from Life

This is your unique chance to get unlimited personal tutoring at a tiny fraction of what it really costs.

Don't miss your once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

Enroll in the Life Drawing Academy now!

How to Draw from Life

By Alexander Ryzhkin

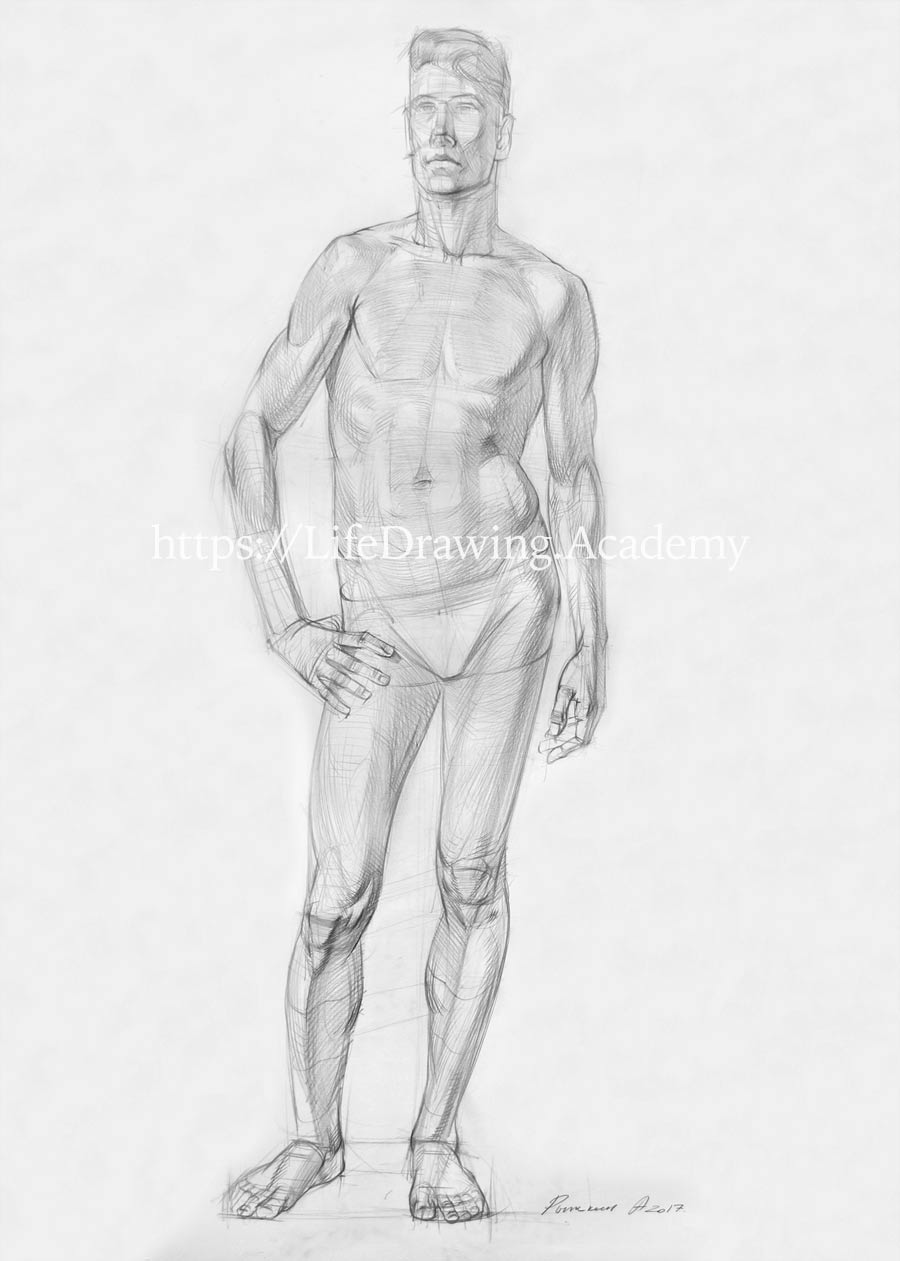

In this video lesson, you will discover How to Draw Human Body.

What we did before is constructive or anatomical drawing. Let's continue with tonal drawing. The light is coming from the top left, and planes facing the light have lighter tonal values than areas turned away from the light. The highlight on the shoulder is one of the lightest spots on the figure. To make it appear so, we need to render areas around it. The top plane of the shoulder is almost horizontal. That is why the direction of pencil strokes also goes horizontally. The side and front planes of the deltoid are vertical, and we render them using different directions of pencil strokes. The top half of the deltoid resembles a cuboid, hence the direction of strokes. At the same time, we can consider this shape not as a cube, but as a sphere and apply rendering strokes along contours that have oval shapes. Both approaches—drawing the deltoid as a cube and as a sphere—are valid and help each other to fully reveal its three-dimensional nature.

Tonal rendering of smaller details is quite a slow job. You need to have enough patience to meticulously render inch by inch of the surface, doing layer upon layer of pencil-hatching. This job also requires a careful evaluation of differences in tonal values between areas that lie near each other. It is important to continue working on the construction of the body, even during tonal rendering. If at any point you feel like you are just "decorating" a figure by applying tones, you need to go back to thoughtful drawing, analysing shapes, and using tones to reveal the construction.

Tonal values, together with direction of pencil strokes, can either describe volumes of a figure or conceal them. Repeating lighter and darker tones that you see on the model is not enough. Such tonal gradations need to be used to portray a figure's construction. You also need to constantly compare tonal values to each other, and, working in layers, render tones gradually. The farther a place from the light-source, the darker it will be compared to the place that is closer to the light.

The style of rendering is like handwriting. It is very individual. You need to work on your style to make it the way you want it to be. You can notice that after a brief rendering of one part of a figure, that part will become very different to the rest. The professional way of rendering tonal values is not to concentrate on one area for too long, but to keep developing the whole figure simultaneously. Wider pencil strokes can go along the contours of big forms, while smaller details need to be rendered in shorter stokes. Big, flat planes can be described in parallel hatching. It is essential to hatch along the contours of such planes.

Here is one tip when rendering planes: Stressing in sharper tones the borders between planes helps to reveal their geometrical construction. At the right side of the chest, there is a border between light and shadow. This core-shadow has to be darker and more pronounced to show the three-dimensional volume of the chest. The chest muscle has a spherical shape, and making pencil strokes along oval contours helps to describe its volume.

Highlights should be kept as white as paper, and erasing those places from time to time will be required to keep the paper clean. The top of the trapezius muscle and the collarbone are rather small areas and have to be rendered with a bit more attention to detail. You need to evaluate different planes in such areas and apply tones according to the relative positions of such planes. It is advisable to render all parts of the body in pairs. For example, the left and the right sides of the neck. The half that is turned away from the light can be shaded in a big shadow that combines different small planes. The model's left shoulder is farther from the light than his right shoulder, and it should be rendered in deeper tones. Once again, the border of the shadow shall be marked more intensively. A big shadow also combines the model's left upper arm and can be rendered in wider strokes. The frontal part of the chest requires some attention to the core-shadow, the lower edge of the chest muscle, and the edge of the ribcage. Pencil strokes should go along contours of those parts. The middle of the chest has a dip between two chest muscles. This dip is portrayed as a darker area on one side and a highlight on the other.

A similar approach can be used to render the middle line of the straight muscle of the abdomen. The diagonal direction of pencil strokes shows the borders of that abdominal muscle. The deep tone of the shadow under the arm helps to expose the difference between the form-shadow and the reflected light in shade. Comparing tones on both sides of the figure, we need to make sure that the balance between the darkest parts is in place by adding additional layers of hatching to make shadows darker. The direction of pencil strokes above and below the waist is different. Above the navel, we see the ribcage from below, and the contours are curved upwards, while below the navel, we see the pelvis from above, and all main contours are facing downwards.

As tonal values are getting darker, you may change from a graphite pencil grade to a softer one. For example, we went from HB to 3B in this drawing. Having more than two or three pencil grades in one drawing is overkill. You need to train your hand to vary tonal values by applying different pressure on a pencil rather than rely on drawing materials for difference in tones.

In constructive drawing, we were looking for edges of forms using lines. In tonal drawing, we are looking for edges of tones. In the beginning, we were using quite a lot of virtual helping lines in constructive drawing. We left those lines un-erased. In tonal drawing, such lines are vanishing under layers of hatching. So, do not be afraid of marking lines during constructive drawing. As long as they are in the correct places, they will help in tonal rendering. The more layers you do in one drawing, the more freedom with direction of lines you may have. Layers of cross-hatching will visually merge into deeper tones. The main thing to observe is building tonal values gradually, layer by layer. You may also see that at all times this drawing looks complete. It is not finished yet, but it is complete as an artwork.

We do not "decorate" the shapes of the figure with tones; instead, we "sculpt" the figure's planes and the borders between them using tones as the instrument of drawing. The anatomical structure of a human body should be constantly in your mind, and the drawing process has to be meaningful. As soon as you stop asking yourself such questions as how this tone helps to describe the anatomy and the construction of the body beneath the skin, you are not drawing skilfully but copying what you see on the surface. This leads to inevitable mistakes in drawing. Also, do not concentrate on one area of a drawing for a long time. Go from one place to another as often as required, so your eyes do not get used to one spot and stop seeing it with a fresh look. Pencil strokes can also define directions instead of contours. For example, long strokes can point to where muscles originate and where they insert, what parts of the body they link, or help to depict the dynamic diagonals of a human figure. In tonal drawing, the core-shadow, which is the border between the form-shadow and mid-tones, is very important. The Old Masters knew about this and left many drawings that suggest that they were starting tonal rendering by finding the borders between light and shadow.

Tonal rendering should go from big areas to small details, then come back to big areas once again. Such a cycle can be repeated as many times as required to achieve the creative task in mind. When working on small details, the approach to shading is very similar to rendering big shapes, but on a smaller scale. All those rules that are applicable to global forms are in full force here as well. When rendering small details, we still need to see and depict core-shadows, reflected light, highlights and casted shadows, and we must apply pencil strokes along contours and build tonal values in layers. Drawing small details is fully applicable when drawing a face. Here's one tip: Do not over-render a face just because it is very characteristic to a model. There's a danger that such a face will look like a mask that has a different style than the rest of the figure. Drawing a portrait is a very specific subject that is fully described in other video lessons of the Life Drawing Class. So, in this lesson, we will mention just a few things on that topic. First of all, because it is a full-figure drawing, you don't have to go into small details of facial features. Describing the big forms of the face is more important. Also, draw a face in the same hatching style that you have used for the body.

Despite the temptation to spend much time drawing a face, you can step back and return to rendering other parts of the body from time to time to keep your eyes fresh for work on the face. When rendering a hairstyle, remember that it has its big volume and should be drawn as one solid object rather that an array of pencil strokes that depict individual hair curls. As a big volume, hairstyle has its core shadow separating light and shadow areas, as well as highlights that can be illustrated with an eraser. Aerial perspective has to be in place when drawing a portrait. For example, ears have to be rendered with less contrast than the nose in a full-face portrait. This gives an illusion that the ears and the back of the head are farther from the viewer than the face...

[ The full lesson is avaibale to Life Drawing Academy members ]

This is your unique chance to get a lifetime academy membership and a dedicated team of art teachers.

Such unlimited personal tutoring is not available anywhere else.